Huw Gwynn-Jones, The Art of Counting Stars, Shearwater Press, 2021.

ISBN 978-1-7399181-0-1. 63pp. £7.

Gwynn-Jones’ biography says he “comes from a line of published poets in the Welsh bardic tradition”, they were high status members of society, who had obligations to praise their local toffs, or an anarcho-syndicalist commune if you like. Well, that’s setting his stall out. Until his recent retirement to Orkney he had never written a poem himself. What reams we could have had from the young, rash lad!

The opening poem, Village, might have been a Tolkienian chimera of the simplicity of rural life, eyeing hobbits harping on about their home brewed stout and peculiar shaped radishes but Gwynn-Jones has enough panache to rouse it through the eye of the needle of history, imagining ages past, the stretch of time’s daily life being a struggle then huddle up next to an open hearth, yet it reads like a Victorian ad for a bucolic life on a city’s smoke-filled train station. His is an Ealing Studios echo, comfy yet you can’t help but think something wicked this way comes. This is the way with memory, perhaps?

yet they dreamt

of a settled place

for the sowing of wheat

a village

where the ghosts of men

might sup and windows listen

to the glide of night owls.

Changing the subject as I turn the pages, I have been fascinated by sleeper trains, or night trains for as long as I can remember. It’s weird, the need for exploration but it passing by whilst you sleep on a juddering colubrine beast, waking in a heady brew of a Liberté, égalité, fraternité Paris or the old bastion of Eastern Christendom Byzantium, or Istanbul to give it its proper name in a city shrouded with many names. Gwynn-Jones shares this witchery with his poem ‘The Lust for Steam’:

I remember another train those ill-lit

nights in December, a handful of boys

in green caps waiting for the gleam

of pistons mighty as God

The imagery of this mystique of power has me swept up in turbines. During the first half of the last century this wouldn’t be just a romantic notion, some would believe it.

This collection is a time capsule, not one buried down beneath where moles fear to tread, no, it’s as if I’m flicking through the writer’s family album revealing a cast of characters, with the stern grandmother with “her raw wit, / a certain competence and pull / of gravity that caused a small / world her” [Matriarch] and just like a photo album it reveals faces long gone, ghosts. One of the strongest pieces is ‘Mannequin’ where Gwynn-Jones visits his mother’s body in a chapel of rest—

no longer she but a mannequin,

startling, waxy and inert -

the first I’d ever met

in a chapel of rest, lidded

doll’s eyes pleading no more, unseeing as buttons

There’s a rapidly blackening cloud ripping beneath these lines, fear of one’s own departure but not that at its core, the loss we have to carry hunches you in old age.

Gwynn-Jones evocation of his past is provincial yet well travelled on life’s spice route, infinity’s wings beat through his nights’ retrospectives.

Grant Tarbard is the author of ‘Loneliness is the Machine that Drives the World’ (Platypus Press) and ‘Rosary of Ghosts’ (Indigo Dreams). His new pamphlet ‘This is the Carousel Mother Warned You About’ (Three Drops Press) and new collection ‘dog’ (Gatehouse Press) will be out this year.

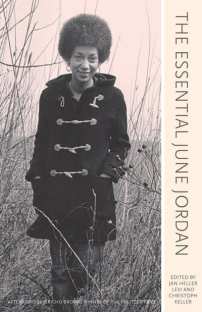

The Essential June Jordan,

Edited by Jan Heller Levi and Christoph Keller,

Copper Canyon Press, 2021.

ISBN: 978-1-55659-620-9. 256pp. $18.00.

June Jordan’s poem, “These Poems,” from her 1974 collection, New Days begins:

These poems

they are things that I do

in the dark

reaching for you

whoever you are

and

are you ready?

Indeed, these eighty-two poems, taken from over ten collections, from her 1969 debut Who Look at Me to Directed by Desire, the collection that was posthumously published in 2005 (Jordan died from breast cancer is 2002), all reach directly for the reader, ready or not, challenging us, our convictions, our beliefs, our prejudices. Her tone is blunt, to the point, if at times satirical in exposing the injustices that surround and smother us. Some of her poems seem so contemporary, such as “Poem About Police Violence,” a poem about racist police behavior, from the 1980 collection, Passion. It starts:

Tell me something

what you think would happen if

everytime they kill a black boy

then we kill a cop

everytime they kill a black man

then we kill a cop

“Letter to the Local Police” (from Passion, 1980) makes a similar point. “Song of the Law Abiding Citizen” is more satiric in highlighting social injustice (“so hot so hot so hot so what / so hot so what so hot so hot”).

Violence against women is another theme that feels so current. “Case in Point,” which likewise comes from Passion, describes her rape in vivid language and female silence in the face of that sort of brutality. The previously unpublished “On Time Tanka” begins:

I refuse to choose

between lynch rope and gang rape

the blues is the blues!

my skin and my sex: Deep dues

I have no wish to escape

Other poems address U.S. foreign policy, and while rooted in particular events – Nicaragua, Iraq, South Africa – the hypocrisy is familiar. “The Bombing of Baghdad,” from the 1997 collection, Kissing God Goodbye, describes the horror of war for the Iraqi civilians caught in the crosshairs of American military assault (“we bombed Iraq we bombed Baghdad / we bombed Basra/we bombed military / installations we bombed the National Museum / we bombed schools we bombed air raid / shelters we bombed water we bombed / electricity we bombed hospitals we / bombed streets we bombed highways / we bombed everything that moved….”) Jordan goes on to compare the Baghdad assault with Custer and Crazy Horse at Little Big Horn. The poem ends:

And this is for Crazy Horse singing as he dies

And here is my song of the living

who must sing against the dying

sing to join the living

with the dead

Jordan’s frustration and anger are evident in poems like “I Must Become a Menace to My Enemies“ (which is dedicated to Agostinho Neto, President of the People’s Republic of Angola in 1976) - from the 1977 book, Things That I Do in the Dark – and the ironically titled “Why I Became a Pacifist” from Haruko/Love Poems (1994). The latter begins:

Why I became a pacifist

and then

How I became a warrior again:

Because nothing I could do or say

turned out OK

I figured I should just sit

still and chill

except to maybe mumble

“Baby, Baby,

Stop!”

AND

Because turning the other cheek

holding my tongue

refusing to retaliate when the deal

got ugly

And because not throwing whoever calls me bitch

out the goddamn window

And because swallowing my pride…

The poem goes on to spell out the conclusion:

I pick up my sword

I lift up my shield

And I stay ready for war….

The satiric “In Defense of Christianity: Sermon from the Fount,” a previously unpublished poem, makes a similar point. It begins, “And seeing the multitudes / he closed up his laptop / computer.”

Blessed are the proud and mighty: For they shall conquer

the earth and subdivide

and subjugate the peoples who abide

therein!

“Kissing God Goodbye,” the title poem from her 1997 collection, expresses a similar skepticism in a similarly satiric tone.

The emperor of poverty

The czar of suffering

The wizard of disease

The joker of morality

The pioneer of slavery

The priest of sexuality

The host of violence

The Almighty fount of fear and trembling

That’s the guy?

As Pulitzer Prizewinner Jericho Brown notes in her “Afterword,” June Jordan’s poetry is committed to Black vernacular. “She understood the phrase ‘standard English’ to be a racist one,” Brown writes. Take the poem, “A Runaway Li’l Bit Poem,” from the 1985 collection, Living Room. The poem begins:

Sometime DeLiza get so crazy she omit

the bebop from the concrete she intimidate

the music she excruciate the whiskey she

obliterate the blow she sneeze

hypothetical at sex

You can feel the pleasure she takes in the patois. We can also feel her pride in her poem, “Shakespeare’s 116th Sonnet in Black English translation,” from the posthumous collection, Directed by Desire. Shakespeare’s poem starts:

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments. Love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove.

Jordan writes:

Don’t let me mess up my partner happiness

because the trouble

start

An’ I ain’t got the heart

to deal!

That won’t be real

(about love)

if I

(push come to shove)

Just punk

Love, indeed, for all her anger and frustration, is at the heart of Jordan’s “message.” Her “Poem on the Death of Princess Diana” (from Directed Desire) makes the point:

At least she was riding

beside

somebody going somewhere

fast

about love

The editors of this collection, Jan Heller Levi and Christoph Keller, have done an amazing job arranging Jordan’s poems from almost four decades of work into thematic chunks that reinforce their points by their sheer proximity, culling these poems from hundreds, to assemble the essential work of an essential poet and activist.

Charles Rammelkamp

To order this book click here

Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore, where he lives, and edits The Potomac, an online literary journal. http://thepotomacjournal.com. His photographs, poetry and fiction have appeared in many literary journals. His latest book is a collection of poems called Mata Hari: Eye of the Day (Apprentice House, Loyola University), and another poetry collection, American Zeitgeist, is forthcoming from Apprentice House.