Clare Shaw, Towards a General Theory of Love, Bloodaxe, 2022. ISBN 978 1 78037 604 2.

79 pp. £10.99.

Clare Shaw’s eagerly awaited latest collection is woven through with poems about a tenderly observed ‘Monkey’, who at one level is a poignant commentary on Harry Harlow’s experiments on attachment and loss in baby primates, and at another level a metaphor for the human need for love and belonging; how love is found and lost, sometimes in unexpected places.

There is a trend in contemporary poetry for collections to be shaped and held together by a recurring theme, motif, symbol, or even animal (the crow in Max Porter’s Grief is the Thing with Feathers comes to mind, and in Shaw’s previous collection Flood, the river Calder held the same metonymic significance.) In this collection, Monkey pops up almost as a familiar, or one of Philip Pullman’s daemons; an alter ego as much as anything else.

Shaw takes no prisoners; as a previous ‘service user’ of Liverpool psychiatric services in her youth, and as a therapeutic practitioner now, she writes from the heart, but always with keen attention to the craft which lifts such deeply personal poetry above the solipsistic. ‘abcedarian’ ends with a hyperbolic response to the commonly asked question ‘on a scale of 1-10 didit hurt/yes/ten/zillion’; here, the elision, and breaking, of words captures powerfully the rupture in both the mental processes and ability to communicate caused by aphasia.

As so often in Shaw’s poetry, wild landscapes offer their own compassion and comfort: ‘If you couldn’t’ say how alone you were,/there’d be the moor,’ she tells us (‘The Night your Mother Died’); ‘the silence of lakes … the wind on the moor’ appear in ‘An Empirical Examination of the Stage Theory of Grief’. In ‘Rhosymedre: Prelude on a Welsh Hymn,’ features of the natural world actually become merged with the poet’s emotional experiences, in a way which skilfully captures the holistic experience of grief, how it permeates every cranny of our selfhood: how pain ‘can be sunlight’ and ‘grief is white blossom … a lake I will walk by forever.’ This poem is one of several which refers to a conventional spirituality; ‘The Day Thou Gavest’ being an example of a different sort of integration; the poet’s own words and those of a previous poet (here John Ellerton who wrote the words for the hymn in 1870).

But this collection also represents a deeply embodied interpretation of love, in its involvement of the whole human person. Physical love and its expression are presented as holy, whether the moment of birth where ‘I was holy /and going to make it’ (Midwife, Calderdale General Hospital’), or an erotic moment ‘Back then// [when]we were not ashamed of our skin./We lay in the grass and you smelt of sun./: ‘ And what happened between us was holy.’ – a transformation into beauty of the nightmarish apocalyptic image of Bosch’s painting ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’ which forms the cover for the book.

The final poem brings together Monkey and William Blake, in another mystical encounter, offering a joyous, creative, resolution to an at times darkly brooding collection; it is through ‘scribbling on the pages of his book’ that ‘the two of us dancing/and Monkey is grinning’.

Thoroughly recommended.

Hannah Stone

To order this book click here

Hannah Stone is the author of Lodestone (Stairwell Books, 2016), Missing Miles (Indigo Dream Publishing, 2017), Swn y Morloi (Maytree Press, 2019) and several collaborations, including Fit to Bust with Pamela Scobie (Runcible Spoon, 2020). She convenes the poets/composers forum for Leeds Lieder, curates Nowt but Verse for Leeds Library, is poet-theologian in Virtual Residence for Leeds Church Institute and editor of the literary journal Dream Catcher. Contact her on hannahstone14@hotmail.com for readings, workshops or book purchases.

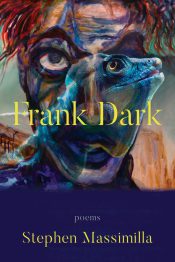

Stephen Massimilla, Frank Dark,

Barrow Street Press, 2022.

ISBN: 978-1-7366075-6-5. 106pp. $18.00.

Frank Dark sounds like the name of a mysterious gunslinger come to the bleak American wasteland to administer justice in whatever small and ultimately inconsequential way he can. Gritty, unsmiling, grim. In fact, though, instead of names, the words are adjectives, frank and dark, but just the same they convey an element of noir – despondent, austere, sinister, apprehensive.

But imagine Frank Dark really is the mysterious gunslinger. His motto might be the first lines of Stephen Massimilla’s poem, “Misdirection: A Poem,” which comes in the final section of this brooding, philosophical collection:

A genius said that without God, people would believe

in just about anything. But wasn’t God already almost anything?

If I’d gotten up earlier, the awful roar of the leaf blower

in the rented yard wouldn’t have jolted me

awake.

Frank Dark is already ready to rumble, menaced by modern “improvements” that are more hassle

than they’re worth, our civilization going to hell with its environment-raping gadgets and technology. The very cover of the book, a collaboration between Massimilla and Myra Kornfield,

suggests his dark, foreboding verse, depicting a lizard profile overlapping a partial human face, like a bad dream framed in a stark, dark background of bruised sky and bleak landscape.

The eponymous poem, also from the fourth section of Frank Dark, echoes the mood of the cover art:

Where you emerge from no mist

No false choice of sunlight to slip

Into mind, where the death-weather persists

To distress and confuse

In all its starved hearts

In all its strangled frame

Massimilla’s landscapes – more often seascapes – are vast and

apocalyptic, full of “death-weather.” He’s concerned with the global condition, not necessarily particular circumstances, but the locations are specific and vivid – the Louisiana coastline or the

North Sea, the Red Sea, Long Island Sound, Gravesend Bay and many others. The poems describe dreary and hopeless, desolate scenes. “What I Was Then,” “Harbor’s Edge,”

“Almost Past That,” “Lowell Harbor,” “Oil Flew into the Sea,” “Slow Storm,” “Full Cooler,” “Above the Insomniac Sea”: these are only a few of the titles of such

poems.

Massimilla’s mentors – the Virgils to his Dante as he goes through the inferno that is our modern world – are the Italian Hermetic poets, like Eugenio Montale, Giuseppe Ungaretti and Salvatore Quasimodo. The central theme of the Hermetic poets, who wrote in the post-World War One era, is the desperate sense of loneliness modern man experiences, having lost touch with the ancient values. This is certainly a theme in Massimilla’s work as well. Two of the poems in Frank Dark, “The Hitlerian Spring” and “The Storm,” are After Montale. Like Montale’s Ossi de sepia (“Cuttlefish Bones”), Massimilla presents a tragic vision of the world as a hostile, barren, desolate place. “In the Clinic,” one of a handful of poems in which Massimilla features sick and dying people in hospital settings, is likewise After Quasimodo. Hermeticism also featured constant emotional introspection, which pretty much fits Stephen Massimilla to a T – “the destruction which you carry carved inside you / and which cleaves you / closer than love ever could to me, strange sister,” he writes in “The Storm.”

But Massimilla is also a lyrical genius. Massimilla’s poetry is musical and a pleasure to recite, despite the gloomy themes. The internal rhyme is impressive and euphonious. In “Map of Scars,” another of his “geographical” poems, he writes the lines:

the scavenger’s double, having fiddled with oblivion, quitting

this shore, lifting over the ships, the persistent hiss of waves…

Those lines sing! The assonance of the “id-iv-it-ip-iss” is simply delicious. Another seascape poem, “Quarantine Fragments,” concludes with the songlike verse,

stepping plashlessly into the dim dawn

like the dissolving wake of a boat,

the receding odor and sound of the shore

drowned out by the battered sea behind me.

More assonance, more alliteration. More wasteland, too. Or take the poem, “Intermezzo,” with its “Among the unmindful and unmusical / love means scraping for reassurance.” Lovely to say, if a bit depressing to contemplate! “You and I hear only in the air. Swiftlets whistle in the shiftless / pitch, echolocate,” he writes in “Inscape.”

The sonnet, “Northern Anniversary,” set in Scotland – Massimilla is truly all over the map in Frank Dark, in a remarkable and moving way – is a nimble and exquisite example of the form. The first quatrain reads:

Willow banks of Scotland are phantom fountains

thinned in wind; coal-black spires of Glasgow

still whispering near stacks, hills and mountains

mooned in green haloes the last sky now

(“behind us,” completes that sentence) and the concluding couplet reads:

and so remind us: don’t survive. Relax

as winter closes in behind our backs.

Hermeticism was part of the Symbolist movement, which used symbolized language to express individual emotional experience with a subtlety that all too often made the poetry obscure, subjective, and difficult to understand. Massimilla sometimes seems to be deliberately hard to comprehend – unless that’s just me!

Or maybe “Frank Dark,” the gunslinger, has the last laugh on us, after all. In the poem called “Misdirection: A Poem,” Massimilla writes that “Most poetry is at best

the province of such unprofitable questions, or something

even bleaker. I’ve often thought that writing poems could be a way

of imposing one’s inexplicable misery on others. It’s possible

to delight in that kind of misery?

Frank Dark is a remarkable achievement.

Charles Rammelkamp

To order this book click here

Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore, where he lives, and edits The Potomac, an online literary journal. http://thepotomacjournal.com. His photographs, poetry and fiction have appeared in many literary journals. His latest book is a collection of poems called Mata Hari: Eye of the Day (Apprentice House, Loyola University), and another poetry collection, American Zeitgeist, is forthcoming from Apprentice House.