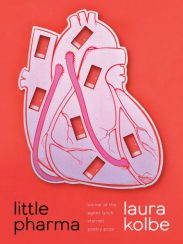

Laura Kolbe, Little Pharma,

University of Pittsburgh Press, 2021.

ISBN: 978-0-8229-6672-3. 128pp. $18.00.

Winner of the Agnes Lynch Starrett Poetry Prize for a first full-length book of poetry, awarded by the University of Pittsburgh Press, Little Pharma is a dazzling display of imagination and versatility with language.

While a good deal of the poems

take place in medical settings – we encounter Kolbe’s fictional alter-ego, Little Pharma, in medical school, in the lab, in the emergency room and elsewhere – arts and crafts also spark her

poetry.

As opposed to Big Pharma, that monolith that dominates the

economy and health care, Little Pharma is a cog in the wheels. She makes me think of Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times, overwhelmed by forces bigger than she. A medical ethicist as well as a

physician, Laura Kolbe understands the underlying fears that plague patients and the ethical implications of treatment. Nine of the forty poems in this collection have “Little Pharma” in the

title – “Little Pharma Encounters the Spine,” “Little Pharma as Lady Macbeth,” “Little Pharma’s Course in Sonography” among them – and a handful of others seem to be from Little Pharma’s point of

view. Little Pharma worries that she’s inadequate to the Herculean task of saving lives, overwhelmed. “Little Pharma’s Research” begins:

Sometimes when I leave the lab what’s outside

seems some detail of anatomy still, as if always

the metal gurney underlay the day.

The first section of poems highlight the life-and-death stakes involved. Two of the

poems are titled “Intensive Care,” and a third, a prose poem, is called “Buried Abecedary for Intensive Care.” This poem begins, “It’s called an awakening trial when the pleasanter drugs stop.” Kolbe

goes through a grim alphabet of consequences and conditions. “It’s called hipaa when no one tells.” “It’s called query when insurer and the bank won’t tell.” “Called weaning when the fentanyl hangs

salivary at the chin of the bed.” “Called zeroing out when they reset the machines for the next body.” In “Shades Pulled Down” she writes:

The woman wanted the exact meaning of “significant”

alongside emphysema. I think it just means no kidding,

but what do I know.

You can feel the patient’s desperation, and her sneaking

suspicion that the doctor isn’t telling her everything, but how much of the mystery can a physician really know, how much, ethically, can she divulge? The poem

begins:

I am showing a woman the outlines of her last

flirtation – her lungs taking in more than they care to

return, holding the last sip of every breath, nursing it,

the wet air like the liquid penny at the bottom of a

warmed-over coke.

“After the PET Scan” and “Little Pharma Encounters the Spine” show us similar scenes of illness and desperation and the doctor’s moral quandary, there to ease suffering but feeling inadequate to the task. “Puck in Oncology” shows us another woman ravaged by cancer and the helplessness of the physician.

In “Little Pharma on Rooms” the doctor feels guilt at her inability to remember all the names of the suffering in the vast hospital. “She thinks in a smaller hospital / She would remember each face.” She considers the couple in Room 707:

Where a couple lay in bed, one sick

The two now faceless in ozone hoods

The room wore its stretch of curtain

Tight and broad like a bandeau in June

Unspeakable honeymoon

Ringing for ginger ale all the time

Similarly, in “Little Pharma Sees Ghosts,” she experiences pangs of regret for not having caught an illness in time, prescribed more accurately.

If she had ordered blood at six and again at nine

If she had felt for a liver when the eyes rolled back

“Dissecting Blade” is one of those poems that feels like it implicitly involves Little Pharma, though she’s not mentioned by name. It’s an extended metaphor about the scalpel as a sort of religious artifact: “how the sword hilt said, / Biorhtelm made me, Sigebert owns me.” As she clarifies later on about the scalpel: “a tool is a holy thing.” This poem harks back to the first poem in the collection, “The Tower,” where she enumerates the tools of the trade, not unlike a knight’s armor – stethoscope, gavel, light, funnel, “A list of every kind of fire, each paired to a telephone.”

About midway through Little Pharma, Kolbe takes on other themes. Two poems titled “On a Bill Traylor Drawing” are inspired by an exhibition at the Smithsonian of Traylor’s work. Traylor was a black man born into slavery in Alabama. In his late eighties he took up pencil and paintbrush. When he died in 1949 he left behind over a thousand works. “Three Designs for Anni Albers” is an homage to the Black Mountain College textile artist, a weaver who inspired a reconsideration of fabrics as an art form. “Die Kunst der Fuge” (J.S. Bach’s “The Art of Fuge”) is a suite of poems set on a Navajo reservation that likewise focus on Native work. “On Lost Art” was likewise inspired by Black Mountain College, an exhibition at the Institute for Contemporary Art in Boston called “Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933-1957.”

Kolbe is nimble with language and imagery. Some examples I’d like to point out include: “I sealed them away / with all the haste of Novocain,” in “Other people’s boyfriends”; “listen to the driveway gravel / seltzering under // the car you’d sent” in “Home Alone,” and finally, from the poem “Imagining Marriage [We visit our elders]” (there are three poems called “Imagining Marriage” in the final section, another departure from Little Pharma): “I’ll be flexing blood

from stones, to no end but to say I could

and die. Why must we come from anyone,

I’d like to know, when we could so easily

have hatched from crusts of planets

where being bubbles up like a soapy,

moonstruck thought?

Why indeed. Laura Kolbe’s poems are both intense and philosophical, allusive and elusive, artistic, and grounded in life. Little Pharma certainly deserves all the awards it can get.

Charles Rammelkamp

To order this book click here

Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore, where he lives, and edits The Potomac, an online literary journal. http://thepotomacjournal.com. His photographs, poetry and fiction have appeared in many literary journals. His latest book is a collection of poems called Mata Hari: Eye of the Day (Apprentice House, Loyola University), and another poetry collection, American Zeitgeist, is forthcoming from Apprentice House.