J. R. Solonche,The Eglantine,

Shanti Arts, 2023. ISBN: 978-1-962082-00-6. 118pp. $15.95.

To claim that J R Solonche is highly regarded as a writer is not to overstate the case. The fact that he has been nominated for the Pulitzer Prize no less than three times is an incontrovertible testament to his standing in the field of poetry. Furthermore, his reputation is built upon a Stakhanovite output. Since the beginning of this century he has published over 30 books. He is a veritable one person poem factory but rest assured this is an operation where quality control procedures are rigorously applied.

Another claim that can be made for him is that he has a distinctive voice. Such an assertion is made so often it risks becoming valueless. With regard to Solonche, however, it is fully justified. He has a style which is instantly recognisable although a consistent voice is not rigidly adhered to. He can be wry and sardonic: a poem like ‘I Hate “I can’t complain”’ gives vent to an outburst of spleen concerning a common expression. Other times he can be whimsical: ‘All Right’ is a dialogue poem (another Solonche trademark) in which the poet converses not only with a talking squirrel but one that is dead too. Another of his guises is the persona of the wise fool, operating as a Mulla Nasrudin foil. In this his strategy is to displace fixed perceptions with the jolt of a Zen awakening and always in language that is lucid and accessible.

Such characteristics might imply that Solonche’s work is unsophisticated when in fact it is quite the opposite. Solonche has an acute awareness of what French critical theorists of the last century called the deja lu, ‘the already read’. He frequently and keenly draws upon this reservoir, realising that creative endeavours are as much immersion as expression. For instance, his ‘Short Conversation with the Sun’ is a clear reference to Frank O’ Hara’s celebrated ‘A True Account of Talking to the Sun at Fire Island’ which in turn references the Russian Futurist poet Mayakovsky’s ‘An Extraordinary Adventure’, which also features a dialogue with the sun. In typical Solonche style his conversation is distinguished by brevity and succinctness. The poem is just twelve lines.

Solonche’s engagement with literary sources could not be more explicit in a sequence entitled ‘25 poems beginning with lines by Emily Dickinson’. The opportunity for improvisation is brilliantly exploited though not carried to excess as each poem is a tightly controlled and rhymed quatrain. It almost feels as if Dickinson and Solonche are standing side by side, the reclusive poet offering a few tentative words from her canon before Solonche steps in with his response, sometimes without even allowing Emily to finish her observation:

Delight is as the flight

leave it there, right there.

Do not say what it might.

Just leave delight hanging in the air.

The whole sequence would make for a wonderful staged event.

A similar dynamic is at work in another suite of poems ‘The Influence of Fifteen Anxieties’, which references Harold Bloom’s The Anxiety of Influence, and gently satirises it. All the examples of the anxieties Solonche faces are so unremarkable the effect is bathos (but the kind to make you chuckle rather than groan) as opposed to the existentialist struggle outlined by Bloom. I suspect Solonche’s view is Bloom’s thesis of latter day writers struggling to resist the influence of their predecessors is not such a big deal. The following example is characteristic:

I cut myself shaving this morning. It took a

long time for the bleeding to stop.

I know it’s foolish, but for a moment, I

thought I was going to bleed to death.

While all the traits we expect from Solonche are there to enjoy in this collection, three intriguing poems stand out from the rest. The first of these is the title poem itself, a prose poem that has a lyrical intensity not always apparent in Solonche’s work. The opening of ‘The Eglantine’ creates an atmosphere that is oneiric, softly delineated but exerting a mesmerising influence:

The last word you hear as you leave the room is the word you remember. It is the word that becomes your shadow for an hour, that shares your shape, that you hear over and over again, that becomes a bell to warn you of a place without meaning. The last word you hear as you leave the room entangles you in sweet briar.

The repetitions and parallelisms have the power of music, softly modulated but incisive, like a slow moving, sombre and bittersweet piano sonata.

In contrast to ‘The Eglantine’, the other two poems are more overtly oratorical. ‘I want to know why there is so much to care about’ and ‘I wanted to make a covenant with the wind’ are placed apart in the collection, but obviously from their titles echo each other, resonating like companion pieces. Both poems employ the simple but time honoured device of anaphora, the repetition of words or phrases at the beginning of successive clauses. Quoting lines in isolation cannot do the poems justice as they have to be experienced holistically because their impact is based on a technique that relies upon an accumulative effect. What is not in question is the power of these poems. They are stunning in their impact, enlivened with a powerful, rhapsodic energy. If they point to a new direction in Solonche’s work, then they are to be welcomed.

For those readers who have not encountered Solonche before, The Eglantine offers an excellent entry point into a unique literary experience that will amuse, entertain, make one see the world anew, subvert expectations and, more often than Solonche is given credit for, touch the heart. Those of us who are already familiar with his work will need no urging to re-engage with a tried and trusted brand or, if you prefer, an old friend.

David Mark Williams

To order this book click here

David Mark Williams writes poetry and short fiction. He has two collections of poetry published: The Odd Sock Exchange (Cinnamon, 2015) and Papaya Fantasia (Hedgehog, 2018). For more information go to www.davidmarkwilliams.co.uk

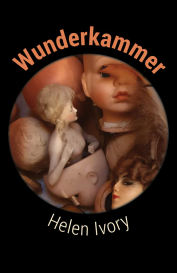

Helen Ivory, Wunderkammer,

Madhat Press, 2023. ISBN 879-1-952335-57-0. 219pp. £20.00.

This lavish feast of the eerie, the surreal, and the downright frightening pulls together Ivory’s five extant Bloodaxe volumes, together with her publications by

SurVision and Gatehouse Press, and a tantalising sample of ten poems from her forthcoming How to Construct A Witch (Bloodaxe, 2024). Of these, her 2019 volume, The Anatomical Venus (which I reviewed at the time in The Lake) introduces us to the concept of the Wunderkammer, from which this current hefty volume takes its title. Waiting for Bluebeard (2013) showcases her preoccupation with female confinement, and the influence of various men in her life and work, themes which re-emerge in the new work. In summary (to quote from my earlier review) Wunderkammer display collections of artefacts gathered and curated by wealthy men, usually including different categories of unusual and grotesque objects such as art work, rare phenomena of nature, inexplicable objects and items from worlds strange or unfamiliar to the purchaser/viewer. They are essentially a means of manifesting both control and ownership, as well as of demonstrating the ‘other’.

It is very good news to find that Ivory is still building and curating her mental, physical and poetic Wunderkammer (and, yes, hats off to Martin Figura for ‘taking kindly’ to the transformation of their entire home into a Wunderkammer.)

Robert Archambeau’s introduction to the book (which sadly contains several typos); is shaped in five questions; Who? What? When? Where? And Why? This is an effective way into Ivory’s mindset and creative energy, for those unfamiliar with her work. The never-far-beneath-the-surface sense of the uncanny and the ‘thin’ spaces (represented here by ‘Séance Night’ among so many other poems) is explained; also we learn more about Ivory’s use of diorama, ‘like the ones she made in art school.’

It is therefore all the more interesting to see the inclusion of eight images of collages by the poet/visual artist. Close examination of these disclose more about Ivory’s preoccupations; ‘look on who will’ lines up eyeballs, fringed with scary lashes, reminding us of the perennial issue of (male/othering) gaze. And her intense connection to the female body and its physiology allowed me to see in the art nouveau swirls and moths of ‘what book do you want’ a formalised image of the female reproductive system. Among the forthcoming release, two poems directly address issues of female physiology in their titles: ‘The Menstruous Woman’ which cites Pliny’s received wisdom that ‘bees, it is a well-known fact, will forsake their hives if touched by a monstrous woman’ – yes, why not blame us for that, as well? ‘The Change’ will resonate with any uterus-owner who experiences the phenomenon whereby:

every night your hormones throw a party

you don’t want to attend.

In these most recent poems, the anger felt and often suppressed by women is given free rein:

You’ve earnt this wrath, don’t squander it

on slapdash chores and sundry empty

in the hollow of your living room.

(‘Spirit of the Storm’)

Of these new poems, ‘Resistance Spells’ speak most powerfully. The afternote giving the United Nations definition of violence against women shows how very political Ivory’s work is, at the macro and micro level. When do we not need to hear that “This is when you stop saying sorry” in sororal solidarity for

the one who bit her tongue so much

her words were cancelled out.

Open to all readers of whatever gender, though, is the message that poetry changes things, empowers, enlivens: all you have to do is remember that:

This is furthermore

a lesson in self-conjuring.

Hannah Stone

To order this book click here

Hannah Stone is the author of Lodestone (Stairwell Books, 2016), Missing Miles (Indigo Dreams Publishing, 2017), Swn y Morloi (Maytree Press, 2019) and several collaborations, including Fit to Bust with Pamela Scobie (Runcible Spoon, 2020). She convenes the poets/composers forum for Leeds Leider, curates Nowt but Verse for Leeds Library, is poet theologian in Virtual Residence for Leeds Church Institute and editor of the literary journal Dream Catcher. Contact her on hannahstone14@hotmail.com for readings, workshops or book purchases.

Patrick Woodcock, Farhang Book One,

ECW Press, 2023. ISBN 9781770417519. 144pp. $21.95 CAD.

Patrick Woodcock’s new book of poetry, Farhang Book One, contains 103 twenty-eight-line poems organized into five sections. Although Woodcock has been in 56 countries over the past three decades, this book focuses on the following fifteen in order: Poland, Lithuania, Russia, Iceland, Bosnia and Herzegovina, The Sultanate of Oman, Saudi Arabia, Colombia, The Kurdish North of Iraq, Fort Good Hope (Canada), Azerbaijan, The Republic of Georgia, Tanzania, Kenya, Rwanda and ends in the small Inuvialuit hamlet of Paulatuk in Canada’s arctic. From a recent interview I read, this is the first of three books and the darkest thematically. This is the beginning of Woodcock's “Tragic Comedy.” But unlike Dante’s religiously compartmentalized books, Woodcock is moving from humanity in book one, to the natural world in book; the third book will be voiced by a narrator alien to our world. If the other two books are as moving as this first one, then Woodcock will have to be considered a poet of considerable standing.

What I find most exciting about Farhang Book One is that Woodcock’s craft matches the time and effort he put into creating them. Only a poet who has lived in Poland and immersed himself in the country could write the following sentence about the horses in Wieliczka:

He only wanted to be wind-beaten again, and not circling

within their time – to gallop out of his gloom,

glossy and untethered –

freed from the subterranean travesty

where the weight of political plots

amongst pillars of salt

rests upon royalty

winding into

windless time, raising

and lowering the morally arched and physically frail.

The continuous push forward in one sentence, with the occasional grammatical and punctuated pause and use enjambment, mirrors the struggle of the horses tasked with walking in circles in the dark for hours on end to raise and lower salt logs and people. The beauty of Woodcock’s book is that there are stunning passages like this on each page. In the poem, “Goodbye Zanzibar Penal Code 1934” Woodcock not only decries the homophobic law that help criminalize homosexuality in Tanzania, but also the poverty suffered by these same communities and how they were forced into helplessness due to extreme poverty paired with a surplus of cheap alcohol (sadly, a theme that occurs in more than one poem and more than one country):

I fear for your home, and the enmity

exhausting it,

I’ve seen barleycorn, and the barely born

unfed in it

Woodcock volunteered in the impoversished ward of Baraa in Arusha, Tanzania for two years at a government primary school. It was at this school and the walks to a from it that Woodcock saw the joy in the children’s eyes transforming into the hopelessness of those robbed of their childhood.

As a Kurd, I found myself drawn to the poems written about Kurds in this book. Woodcock is no stranger when it comes to writing about Kurds. His eighth book, Echo Gods and Silent Mountains, was written solely about the two years Woodcock lived in the Kurdish North of Iraq and the first section of his ninth book, You can’t bury them all, contains seventeen poems about the Kurds in a section called “Yan Kurdistan…Yan Namam” (Give me Kurdistan or Give me Death). In Farhang Book One Woodcock continues to write with empathy, compassion, and beauty about the Kurds. There are ten poems specifically about the Kurdish community along with numerous other poems where our struggles are mentioned. He writes about visiting Assyrian reliefs with friends and how some of these friends limped due to months of torture by foot whipping. He writes about the streets he walked and what he saw only a daily basis. But it is the two poems he wrote about Halabja that gripped me since I am currently in Halabja visiting family.

The poems "Baath’s Members are not Allowed to Enter" and "Orbs Terrify Me Now," demonstrate his deep familiarity with Kurdistan and his ability to convey the experiences and emotions of the Kurdish people. His work reflects historical awareness and a commitment to accurately representing the tragic events of the genocide with respect for both the victims and survivors. In "Baath’s Members are not Allowed to Enter," Woodcock’s meticulous attention to detail and historical accuracy are evident in his portrayal of the Halabja genocide. He conveys the gravity of the situation by describing the victims, a statue of a woman seemingly guarding the tombstones, and the scale of the tragedy with precise numbers taken from numerous plaques. But Woodcock knows that we sometimes become overwhelmed by statistics and lose the human tragedy behind the digits, so he ends the poem by addressing a nameless child who left a toy gun on the ground he discovered on the outskirts of Halabja. This movement from the statistical to the personal hammers the loss home:

I wanted to find the child who left it. were you defending

your family from what fell? Did you have a brother or sister?

A cow? Did I walk past you in the memorial? Did you cry

when you learned you can’t shoot gas?

In "Orbs Terrify Me Now," Woodcock goes beyond describing the genocide and paints a broader picture of the region. He uses striking imagery to convey the landscape, such as mountains that look like "rotten turtles with cracked shells" and "power lines, limp and swaying like the dangling necks / of goat roadkill.” These lines showcase his deep connection with the land and the emotions associated with it. The poem ends in a cemetery where various shapes have now been transformed into triggers, something the local community must struggle with on a daily basis:

A triangle was a limb, an arm, a knee or elbow. Orbs were terrifying

to address; they were the bubbles withing foam within mouths within

children.

Patrick Woodcock’s Farhang Book One is more than the poems about the Kurds. It is a book where he mourns, celebrates, and eulogizes countries, people and even the architecture he was involved with. He is a poet whose life and poetry centre around learned experience, and from this experience he has fashioned a beautiful and momentous book for anyone who loves poetry and remarkable storytelling. But I cannot help returning to the poems he wrote about Kurdistan. He is not only a great poet, but he is also a great friend to the Kurdish people and one of our finest ambassadors.

Diary Marif

To order this book click here

Diary Marif is a Canadian Kurdish nonfiction writer and freelance journalist living on the unceded territories of the Museum, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations, also known as Vancouver. He is an author at New Canadian Media where he focuses on immigrants' and newcomers' issues, particularly sub-minorities like Kurds, Baloches, and so forth. He also writes for some national and international media about Kurdish issues in the Middle East. He earned a master's degree in History from Pune University, in India, in 2013. He participates in rallies in solidarity with minorities and sub-minorities and fights against racism, advocating for equality and justice. He wrote a few chapter books.