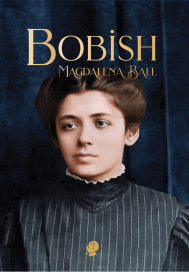

Magdalena Ball, Bobish,

Puncher & Wattman, 2022.

ISBN 978-1922571601. 154pp. £12.99.

Who deserves to have their stories told, especially after they’re no longer here to tell us of their journey through this life? Are some lives too small, too constricted, and just too depressing to be kept and related for posterity? Magdalena Ball’s answer is, in her impressive latest poetry collection Bobish, absolutely not! And by the time you finish her imagined verse biography of her great grandmother, you will agree.

Bobish, the pet name for Ball’s grandmother, was born Rebecca (Rivka) Lieberman, in 1907 in the Pale of Settlement, that part of the Tsarist empire where it was not forbidden for Jews and other non-Russians to live. Just utterly perilous, especially during the unofficially tsarist sanctioned pogroms that tore through shtetls (small villages inhabited mostly by Jews), often at Easter, in much the same horribly murderous way that nightriders visited terror, fire, and death on Blacks in the American South during the Jim Crow era. Indeed, it was in reaction to one pogrom that Rebecca’s parents urged her to flee the Pale for America to escape the ultranationalist, fanatically antisemitic murderous bands of “The Black Hundreds”:

Her mother gave her a bag of coins

the brass samovar, told her to pack

quickly.

You didn’t need tea leaves

to read what was coming.

The reference to “tea leaves” is Ball referring to Bobish’s talent for being able to read the future by examining tea leaves, as in the collection’s opening poem, “A Voice to Shatter Glass”:

People lined up at her door

money in closed fists, ready to hear secrets

wrapped in a soothing voice

break the glass.

If Rebecca thought life in New York, with its streets not paved in gold, was going to be any easier, she was quickly disillusioned of that hope, in the poem “Mamaloshen” (Mother tongue, or Yiddish):

She woke in a strange place

they called it heym

speak English

forget your mother tongue.

That forgetting is the price the newly arrived to America are often forced to pay, and Rebecca was no exception. Moreover, there is also the slowly dawning realization that she’ll probably never see her family again, the fate of so many in an age when to leave for a better life in America or elsewhere was to say goodbye forever to parents, siblings, friends. This loss is made painfully poignant in “Third Avenue EL,” the title referring to the elevated train that ran right by Bobish’s tenement apartment and took her daily to work on the Lower East Side. She waits daily, after work, for a letter from her parents, telling her when to expect them in the New World, to escape the worsening pogroms and the looming World War I:

Maybe tomorrow

she would open her apartment door

with the broken bell and in they would come

tired but flushed from travel, carrying tattered suitcases.

But while waiting, in vain, work was essential in this brave, new, merciless world. So, like so many immigrant women (and men, like both my grandfathers), Bobish worked in the textile trade as a seamstress, specifically at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, which went up in flames in 1911, the bosses locking the doors from the outside because they feared workers were stealing from them and taking cigarette breaks. Luckily, she survived the factory/sweatshop blaze that claimed so many innocent lives, since she wasn’t, for whatever reason, at work that day of the worst industrial disaster in the City’s history.

If dodging disasters was the template of her life in Russia and New York City, her meeting her future husband—a peddler of smoked fish and a musician—was a slow-motion train wreck, as in “Diddikai”:

When he showed up a second time

dancing for her with light feet

that seemed to hover above icy cobblestones

she ignored the warning

spelled by her tea, breath condensed with longing

It’s the old sad story: he’s a charmer all right, but also a drinker, and not a happy, gentle one, using his hands on Rivka (Rebecca) far too frequently and efficiently. But through it all, she keeps going, working, surviving the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, surviving poverty and near starvation, bearing children, a victim of diabetes, never quite giving up hope of seeing her Russian family again, through two world wars, and finally dying in 1957.

If all biographies end the same sad way, that’s not the important thing about them. It’s how their subjects lived, and despite it all Rebecca (Rivka/Bobish) Lieberman lived well. Against great odds she made her way through a ruthless world; never attained fame, but that’s not what she was looking for, just a path to some sort of happiness, no matter how fleeting. She persevered, made the best of things, used her native talents and when the burden finally got too heavy, laid it down. That’s all that can be said of any of us. Magdalena Ball does full justice to her story. Would that all of us had such an eloquent and careful chronicler of our lives.

Robert Cooperman

To order this book click here

Robert Cooperman is the author of over twenty poetry collections, most recently Bearing the Body of Hector Home (FutureCycle Press).

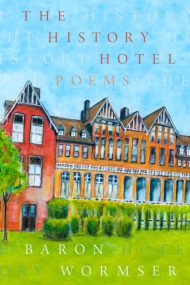

Baron Wormser, The History Hotel,

CavanKerry Press, 2023.

ISBN: 978-1-933880-98-3. 208pp. $18.00.

As the title of Baron Wormser’s new collection of poems implies, time is a major theme of this book. Like an invocation, the five-part collection is prefaced by a poem titled “Brief,” an ambiguous word that means a concise summary statement of what follows but also suggests the fleeting nature of time. (“Out, out, brief candle!” Macbeth cries, referring to life.) “Look!” the poem begins in a tone of astonishment, “I became an old man.” It all happened so fast! Another poem, whose title is the opening line of Shakespeare’s 64th sonnet – “When I have seen by time’s fell hand defaced” – whose subject is a dying (cancer) literature professor, likewise hints at the accelerating nature of time – its “illimitable quickening.”

Not that Wormser laments the way time rushes past, or at least not only. As he writes in the title poem, referring to a dog that patiently waits, “Understanding how time is empty and full and may offer a biscuit,” a life doesn’t simply “pass”; it has its rewards. What are the biscuits time offers? Experience may be the shorthand for all that. History amounts, in part, to memory, and memory extends these biscuits to us, or, as Wormser calls them in the opening poem, “Brief,” “emotional errands.” (“…writing poems in my excited / Leaves-letters-out scrawl – / Emotional errands from witless to wit / and back.”)

One biscuit time has yielded is the memory of his grandmother’s reaction to Marilyn Monroe’s drug overdose death, “On a Foreseen Death, August 4, 1962.” His Jewish grandmother, survivor of pogroms, is dismissive of this “Shiksa who’d wagged it for the world,” but in a different frame of mind, Wormser knows, she might have been more sympathetic toward this woman,

Hollering that she hadn’t asked for this life she’d

Found herself in, as weary of winking at fame’s

Camera but had nowhere to turn, no earth beneath her –

Nothing – something my grandmother might have

Understood…

Other biscuits heaved up by time: the lovely villanelle, “Upon the Death of the Actor, Philip Seymour Hoffman from ‘Acute Drug Intoxication,’” (“Don’t do it. Don’t lose yourself this soon.”); “For Raymond Lévy,” a Holocaust survivor tortured at Dachau, reading about his death on his back porch, in 2014, while a catbird mews in Wormser’s yard; “A Memorable Occasion: Opening the Doors,” an allusion to Huxley’s Doors of Perception, recounts an LSD trip; “The New Wave,” a memory in sonnet form of discussing French cinema from the 1960’s, Godard’s My Life to Live (“existential / Crisis rendered in a faux-documentarian style”); the memory of a “bachelor” uncle (“a word even then, / In the mid-twentieth century, on the way out”), a sort of prototype for Wormser’s own life, we intuit:

All this folk wisdom following me

As I planned how to make my mistakes.

Understanding these poems as “emotional errands,” we read poems like “Ode to Worry,” as universal conditions. “Did Christ Buddha Mohammad worry?” he asks. “How petty this noticing / The small change of aggrieved empathy / Pettier than any petty bourgeoisie.” “On Empire” is an amused consideration of a man mowing his yard – his “empire” (a man’s home is his castle, right?) – the faux sense of power. “NFL Poem (Annals of Male Americana)” is a similarly droll take on the validation sports fans experience, their letdown when the game is over, especially if the home team loses. “Ode to the Stock Exchange” recounts the photos of frenzied traders on the stock exchange floor, their own sense of validation, not unlike a teenage boy’s excitement at seeing girls’ breasts in tight sweaters.

And I wondered how much anything

Could cost when its value was inestimable.

Poems titled “1910” and “1893” underscore the theme of history, of time. Both are poems that involve painting. “1910” features Amedeo Modigliani and his lover, Anna Akhmatova. Some emotional errands outlast time.

Amedeo finds the money for more paint, Anna for ink.

Neither the colors nor the words will fade; they know this.

“1893” is a two-part poem, the first called “Opium Den,” and the second, “Plein Air,” presents a painting instructor conducting his class in outdoor landscape painting, the poem ending in similar triumph as the instructor strolls among his students,

Muttering encouragement yet halting once in a

while

To say nothing, to let some quiet felicity

Sing its unfettered,

chromatic heart out.

Teachers, notably, are central to a handful of poems in The History Hotel. Perhaps “A Certain Teacher Does Some Banking” stands out as the ultimate representative of this collection. It’s very playful, almost dreamlike, which is a characteristic at the center of Wormser’s charm. In this poem,The teacher has some heavy minutes he wants to deposit.

“Not the light ones that evaporate,” he explains

to the teller.

“Not the ones that suggest life is not so corporeal

that seconds are instances of nothing.

Not those.”

The teacher and the teller converse about the transaction, as though they are discussing a mortgage, a loan, renting a safe deposit box or some other quotidian banking business. “Resentment? Do you guarantee that? / Self-doubt? Feckless longing?” After all, aren’t these the heaviest of our emotional errands?

The densest of the biscuits time offers? The History Hotel is philosophical and charming, the work of a master poet that serenely takes the long view of life hope and despair swirled together.

Charles Rammelkamp

To order this book click here

Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore, where he lives, and edits The Potomac, an online literary journal. http://thepotomacjournal.com. His photographs, poetry and fiction have appeared in many literary journals. His latest book is a collection of poems called Mata Hari: Eye of the Day (Apprentice House, Loyola University), and another poetry collection, American Zeitgeist, is forthcoming from Apprentice House.