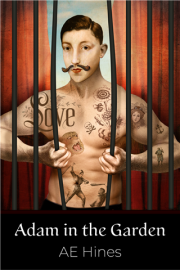

A.E. Hines, Adam in the Garden,

Charlotte Press, 2024.

ISBN: 978-1960558077. 100pp. $18.00.

The story of Adam and Eve and the Garden of Eden is a story of loss. And then Cain kills Abel and the whole world goes to hell. (See “Adam in Another Garden.”) For A.E. Hines, loss and paradise are always in competition. He can be lyrical about sublime happiness but at the same time aware of its fleeting fragility. As he writes in “After the Adoption”:

Perhaps you too have done this?

Found yourself awake on the edge

of so much happiness you fear fate

might intervene.

Adam in the Garden opens in South America, lush, paradisiacal. Edenic, indeed. As he describes it in the poem, “Eden,” “toucans / and motmots, a flock of miniature finches / dusted with pale blue chalk.” The reader vicariously luxuriates in the lush environment. But in that second poem of the collection, “Breakfast in South America,” in which a “great blue-green bird” darts “from cypress to pine” like some heavenly, immortal being from ancient myth:

It’s hard, this morning

to see the fresh orchids, speckled yellow

and pinks bubbling up from the trunks, to see

this bird propped among the red-gold bromeliads

still fusing with the branches—to remember

this bright world, blue and green, is dying.

Certainly, Hines is aware of

his own mortality and the fragility of the people he knows, which gives a tender emphasis to their value and importance in his life. We’ve already seen his son’s vulnerability through his eyes. In

“Fibrillation” a forty-four-year-old friend collapses in a gym, and an EMT revives him with an AED, using the electric paddles “to wake / Phil’s sleeping heart with fire.” Witnessing the horror and

the heroism reminds Hines of his own mortality. He focuses on his own heartbeat, the “fluttering bird” caged in his chest, and “as each / breath leaves this body, and like a small / resurrection,

returns.”

In “Green Satin,” a friend lies in a hospice bed laboring to

breathe.

Perhaps, it’s not the drugs

when you tell me you plan

to come back as a tree, wearing

green satin gowns and scarves

made of wind. No more ridiculous,

you say, than dying, or your wig

teetering from the nightstand.

The images of resurrection and reincarnation in these poems suggest something holy about this one brief life that we live, that living is ultimately what we mean by “paradise.”

“On a Bench by Little Sugar Creek,” written for Matt, is about a friend’s early death.

My friend is dead. Too young. Too

everything. Two baby boys, a husband

who loved him. My friend is dead

and I think I should get up

and do something.

In “Cervical Stenosis” the poet undergoes a spinal operation that makes his vulnerability all too clear, and in “Ocular Migraine” he writes about going blind in one eye “after making love,” sex and death coiled together like a caduceus. Doctors give opinions, mutter about nerve cells and blood vessels, consult MRI tests. Scratch their heads. But the poet confides to his husband:

Sometimes, my head on your chest

and me back in my body—I think,

my mind is overtaken with more joy

than it’s trained to handle.

If this life is indeed paradise, nobody conjures a more convincing picture than A.E. Hines. The birds are particularly vivid, as we’ve already seen in “Eden.” “Hummingbird” (“I watch a small prince, / from green lamé crown to trembling tail, bow / at our feeder in a blurred halo of wings”) and “Fat City Pigeon” (“your steel / petticoat and gray patrician gown”) are two others that highlight magnificent birds, even the humble pigeon. In “The Crow” the poet is on the telephone with a friend when he spies the bird out his window.

We’d been speaking of forgiveness, how when

we finally get around to it, the people

we most need to forgive are gone.

The poet knows that he should “start dialing up the past” – parents, ex-lovers, neighbors. He feels a kind of urgency to repair misunderstandings.

His relations with his parents are especially troubling. He writes about that hell in “The Fall” (“I swore I’d never go back.”), “Family History” (“The way my mother tells it / I ran away. She didn’t shove me / out the front door at sixteen.”), “The First Time She Goes Missing” (“My sister and I call out to our mother, / lost in the Carolina pines.”). But he seeks a kind of forgiveness, even as he can’t forget. There’s an ex-husband who cheated on him, broke his heart. “Find a Friend” employs biblical language to describe the betrayal, likening it to the sharp stone from David’s sling striking Goliath’s temple. The broken faith is “a rock. / Sharp. To the softest part of my head.” “I Give My Friend My Totem” circles the same betrayal.

But life with his current husband is, yes, idyllic. Or if not idyllic, at least compelling. Hines writes about him lovingly in “To My Flirtatious Friend Who Made a Pass at My Husband on Facebook,” “On Monogamy,” “Paper Anniversary,” “The Exhibitionist,” “Red-Eye Out of Atlanta,” and “We sit upright and bound” (“Touching your skin is stealing fire.”). Both men are in middle age now. “Feeling what, exactly? Safe? Yes, and happy….”

In the poem “Bed” there may be some equivocation.

It starts:

My husband despairs of my

obsession

with darkness, wants me to write

happier poems the way he wishes

I’d make our bed when I roll out

in the morning….

His thoughts move on to the

widow next door still mourning her husband, their routines. Some mornings when she stares at his photo, “it’s enough to send her / crawling back into bed.” Bliss can come crashing down at any

moment. Paradise and loss, indeed.

This is particularly true for a gay man, as Hines’ elegy for

Matthew Shepard, “Postcard from the Dead,” grimly illustrates. Shepard was brutally killed in Wyoming in 1998, simply for being gay. “The Night the Lights Went Out in Moore County” is another, though

its tone is defiant, in response to the 2022 terrorist attack on the electrical power grid for the alleged purpose of shutting down a drag show performance.

We’ve labored in the night long

enough

to know how to fashion our own halos.

Make our own light.

Adam in the Garden wavers between hope and despair, soaring sensual gratitude and a bleak awareness of death. Where does this leave A.E. Hines? I like to think he’s resisting the impulse to give up, to admit defeat. He’s like Adam in “Adam Before Eve,” sensing a change coming, but this Adam “gave up on Paradise

too soon: started building parking lots

and condos. Strip malls and atom bombs.

Stopped going out each morning to shoo

that sweet-talking serpent from his yard.

A.E. Hines has not given up on Paradise. But he’s not taking it for granted, either.

Charles Rammelkamp

To order this book click here

Charles Rammelkampis Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore, where he lives, and edits The Potomac, an online literary journal. http://thepotomacjournal.com. His photographs, poetry and fiction have appeared in many literary journals. His latest book is a collection of poems called Mata Hari: Eye of the Day (Apprentice House, Loyola University), and another poetry collection, American Zeitgeist, is forthcoming from Apprentice House.

J R Solonche, God, Shanti Arts Publishing, 2024. ISBN: 978-1-962082-10-5. 108pp. $16.95.

Solonche is so prolific he does not so much launch books as lob them. He has brought out well over 30 solo collections since the beginning of this century. The secret to his staggering productivity is simple: an unrelenting discipline. Solonche does not wait for inspiration to strike. It’s a job of work for him and he never misses a day.

In ‘What all Poets should Know’, there is one line that is particularly relevant to Solonche’s writing practice: “All poets should know William Stafford’s cure for writer’s block”. I have to confess I couldn’t recall what that cure was and had to look it up. What Stafford had to say about this issue was “there is no such thing as writer’s block for writers whose standards are low enough”. Stafford walked his talk and produced around 20,000 poems. Solonche seems to be attempting the same levels of production. I don’t know what his current tally is but with the number of books he has published it must be in the thousands. While one might argue that quality trumps quantity, the remarkable aspect of both Stafford’s and Solonche’s work is that quality is rarely compromised. Their status and reputation as poets attest to that.

The title poem dispels any expectation that Solonche is at all focused on questions of monotheism. It focuses rather on a memory of the poet aged one reclining in a pram pushed by his mother and stopping outside a Catholic church with a white wall. Some might doubt the veracity of this recollection from such a young age but even if the memory is false it does not detract from the impact of the poem. The church is where “God surely, surely must / have lived, and whose hand surely, / surely have held the handle of my carriage / next to the hand of my mother, his wife.” The literalising of God the Father is both fitting and unsettling.

With Solonche one gets the sense of someone who can write a poem at the drop of a hat from any prompt that comes his way. He is, as was once said of Charles Olson, “a great noticer”. This enlivens his work with range and variety though there are core obsessions too: he writes frequently about birds, flowers, butterflies, wind and rain, sunshine, clouds and sky, the whole gamut in fact of the natural world. This might seem to indicate that Solonche is a pastoral poet but that is far from the case: he is too urban, too edgy in his perspective.

He is especially interested in people. Vignettes of both acquaintances and strangers always feature in his work. It would appear that he is particularly primed for chance encounters. We learn in one poem, ‘In the Hardware Store’, that he always carries copies of one of his books with him when he is out and about to give away to any poetry receptive folk he might meet. The book is Coming To. An assistant at Brett’s True Value warrants being handed a copy based on her appearance: she has half bleached hair and piercings.

Sometimes his exchanges are with dead authors. As with his earlier collection, The Eglantine, we are offered another helping of ‘Twenty Poems Based on First Lines by Emily Dickinson’. These range from the decorous to the subversive:

Circumference, thou bride of awe,

“you say, so awe’s the groom.

But it was late – 1884.

What were you smoking up in your room?”

Another aspect of his work that has been highlighted by several commentators is a penchant for aphorism. Sometimes these have the clarity of a haiku but still have the power to intrigue. ‘Wisdom’, for instance, resonates long after its bare three lines have been assimilated:

It is the shadow

that knows the most

about the sun.

Other aphoristic poems, however, seem intended to trip the reader up with a tangled syntax that disables, at least temporarily, an easy interpretation, as in the following:

Second of all, Alfred,

I wanted to be a poet,

like you, more like you

than like you, less

like me than like me.

This definitely requires more than one reading to get a handle on and that is presumably its intention. It does seem to be a little trap for the rational mind but this is in keeping with another aspect of Solonche’s work, a tendency for mischief making.

Returning to the issue of Solonche’s productivity, his poems should perhaps be perceived as images in a montage, or a slide show, where we are only allowed a brief glimpse before passing on to the next slide. Sometimes the transitions are more like variations in a musical composition: ‘Reunited’, for instance, which records the action of wind after rain lifting “the fallen ash leaves / back again into the waiting / arms of the ash tree” is immediately followed by ‘Just as Yesterday’ where the wind is observed performing a similar action. As long as Solonche is able to keep up this level of output, I think our response should be:’ keep ‘em coming’, and like Groucho Marx’s principles, if one or two poems don’t do it for you, rest assured he has others, ones that most certainly will.

Existing admirers of his work can rest assured that God is quintessential Solonche and for this reason the collection also offers a representative starting point for those readers who have yet to avail themselves of the Solonche experience.

David Mark Williams

To order this book click here

David Mark Williamswrites poetry and short fiction. He has two collections of poetry published: The Odd Sock Exchange (Cinnamon, 2015) and Papaya Fantasia (Hedgehog, 2018).