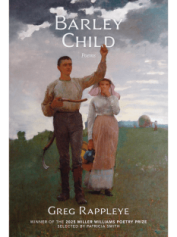

The University of Arkansas Press,

ISBN: 978-1682262696, 2025, 143pp, $19.95.

Chronicling the mid-twentieth century life of an Irish-American family in Michigan, Greg Rappleye, as Patricia Smith, Miller-Williams Poetry Prize judge, notes in her introduction, writes “nerve, sonically explosive lines.” He certainly puts the “fun” in “dysfunction.”

Barley Child is divided into three parts, beginning en medias res in 1960s America before swinging back to the late nineteenth century and the family’s life in Maine and back home in Ireland and their eventual relocation to Michigan. Part three starts there and moves forward in time.

But before moving forward, the collection begins charmingly with a prelude titled “Because I Wish to Avoid Extravagant Claims, and Because God Is Patient with the Unborn”:

Among the nascent embryos, I was a poet

of brass-cut oats, of Dingle cheese, of grilled hake

and muck-tilled potatoes, of soda bread

with salty butter. Then she moaned and I was alive-o…

A barley child, we learn in an epigraph to “Night Work,” the

second poem in the first part, is a child born within the first six months of a marriage, perhaps suggesting a “shotgun wedding,” a couple forced into a union neither may have planned or really

wanted. This may be the case with the protagonist, what the reader is meant to infer.

In any case, Mam and Da are both short-tempered, heavy drinkers, prone to violence. “Age 10, I Escape from the Work Farm and Pursuant to Court Order, Am Recaptured in a Cincinnati Amusement Park” begins:

When Big Da finishes me

with the hickory switch,

he says Your life is too good.

That’s why Mam drinks whiskey.

Frankly, that’s why he drinks whiskey, too.

It doesn’t get any better from there. Indeed, as he notes in the epigraph to the final poem in the collection, “Deus ex Machina,” the sort of divine intervention we all hope for, as in a Charles Dickens novel, never happens in real life. Happy endings, alas, are rare. Instead, Rappleye gives us a relentless, jaw-dropping work of lyrically “explosive lines.” “Checker Cab,” for instance, begins,

It was a deranged midnight brawl

over rent squandered at the harness track,

or perhaps over a mystery woman who lived

in a second-floor walk-up on Rundle

Street.

Story of Mam and Da’s lives. As Rappleye writes later in the

poem,

And surely they raged on, or so claim the neighborhood sagas,

with pikes and axes and epic broadswords,

with daggers and cause-lost flags,

wearing the shirt-mail they’d woven from thick skeins

of alcohol and desire.

Vividly describing the husband and wife “going Medieval” at

each other drives the point home. The alcohol and its inevitable effects are all over the place, in “Arthur Godfrey” (“Mam screws loose the yellow cap / on a shiny bottle and pours a shot glass”),

“Shuffle Puck, 1961” (“Da, sitting at the enormous steering wheel, / would ask in his untrue voice, ‘Dowsie-girl, are ya thirsty?’”), and especially in the third section. As in “Shuffle Puck,” it all

gets mixed up with Irish Catholicism. “The Adoration,” “St. Brendan and the Foaming Sea (1964),” and “I’m Never Told of Family Funerals,” a macabre, darkly humorous tale of placing a

cigarette and shot glass of whiskey in a dead aunt’s hands as she lies in her coffin, all shine a light on the religious observance of the day. The references to JFK are especially touching, from

“Jack Kennedy Whistle-Stops across Southern Michigan” to the allusion to his assassination in “St. Brendan.”

Rappleye admirably includes casual details of the movies and television shows of the era – especially Woody Woodpecker – and the businesses and stores and street names to bring the narrative alive, throughout. The family car, the Nash, is almost a character itself.

Part two delves into the history of his maternal ancestors, immigrating to Maine in the nineteenth century before heading west to Michigan, and again the stories are full of violence and tragedy, revolving around the Pepperell Cotton Mill in Biddeford Maine, where the Gannon family worked, the physically draining ten-hour days. “Cotton House Fire” recalls the burning of the mill, possibly caused by whiskey and carelessness. “The State of Maine” depicts the devastation of the 1918 Spanish Flu epidemic. “Annie Kelly, 25” and “Among the 796 Dead Children at Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home, Tuam, County Galway” involve the scourge of tuberculosis. “The Marsh Harrier” tells the tale of his great-aunt getting knocked-up, nobody sure who the Da is, then sent away to Brittany to have the child; only it dies in childbirth.

“My Grandfather’s Herringbone Cap” introduces Jim Gannon – Gee Da – likewise with a fondness for alcohol – and later, in “Jim Gannon, with Dog and Model A, January 12, 1928,” Rappleye paints a vivid picture of the taciturn, “churlish man.” “Dowsie Gannon, Age 2, in Cleveland,” set in April, 1930, brings Mam into the picture, as the family moves to “far-off Jackson, Michigan, where Gran has a sister.”

And so we come back to Southern Michigan, where Mam’s first husband dies in a tragic accident (“Shotgun Death, with Dodge and Northern Catalpa”) that sends her to Mercywood, a mental institution near Ann Arbor, where she becomes acquainted with the poet, Theodore Roethke, and then the protagonist gets born in “The Song from Moulin Rouge (1953),” “and for an hour or so, I was his / show-off joy.”

Back in part one, in “In a Dream, My Father Decides to Go Ice Fishing,” we learn about the hot dog stand Da opens in the Upper Peninsula, which will become the scene of more violence in the third part. The final break between father and son comes in “Elegy with Blue-Handled Filet Knife,” set in 1974, when the protagonist is about to leave for school in Ann Arbor. In fact, Mam has just left him there at the campus as the poem opens, “still bleeding.”

She knew I was never going back

to Da’s orange-and-brown hot dog stand,

and after Monday night, when he slammed me

against the fryer over a spilled order of onion rings

and kept coming like a Kerry bull

because I wasn’t worth a good-goddam…

And Mam? We last see her in “In Search of a Drinkie, Mam Sneaks Out of Assisted Living to Visit The Blue Marrow,” on her way in her motorized cart to visit with people she no longer remembers are gone. “She does not remember that Connie is dead, Phil is dead, Rick’s doing a hard dime in Ionia….”

With epigraphs from major and obscure Irish writers – Frank O’Connor, James Joyce, Claire Keegan, Karl O’Hanlon – as well as Biblical citations from Numbers, Lamentations, Corinthians and others, Barley Child is steeped in erudition. Citing the Latin names for various creatures of the natural world (Agelaius phoeniceus, the Redwing Blackbird, Circus oeruginosus, the Marsh Harrier, etc.) in other epigraphs, citations from Plato and other ancient scholars, Rappleye brings an element of scholarship to the table as well, fitting for the college professor that he is. Barley Child is indeed a riveting collection, lyrically rendered in a voice at once Irish and Midwestern, full of vivid violence straight out of Quentin Tarantino or Sam Peckinpah, a truly inspired and deeply felt book.

Charles Rammelkamp

To order this book click here

Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books. His latest collection is The Trapeze Of Your Flesh (BlazeVOX Books).

John Gilham, Footprints in the Mud,

ISBN 979-8-31-754573-4, £5.00, 57pp.

For some years, York-based poet was editor of Dream Catcher journal (a role I have inherited from him), so will have read many thousands of poems and short stories submitted for consideration. In line with the ethos of Dream Catcher, here is ‘something for everyone’ – though perhaps not covering every one of Gilham’s listed interests which include ‘ferroequinology’. This slim volume follows three collections of poetry published by Stairwell Books, and includes as well as the poems four engaging brief prose ‘conversations’ with ultra-ego Fosdyke, which include frank details of the hygiene arrangements and ‘butchery and embroidery’ entailed by a heart attack, as well as a pithy dismissal of the latest coronation.

The poems range in tone and content from light-touch witticisms about worms that turn; to tender moments putting socks on as

last night I undressed you

(and you me)

to evaluations of historical layers in ‘Doggerland’, with its musing on separation and change –

what will remain of us

but footprints in the mud?

Gilham’s poetry is accessible and unpretentious. There is a sense of moral reflection in ‘Flying Flashbacks’ in which he relishes the memory of

the slow parade of silver birds

out of the sun in a dawn sky, concluding that

… for now I’ll treasure those gold and silver memories

that cost so much more than I knew at the time.

The poet’s interest in other cultures (including past ones, such as the Roman occupation of Britain, manifest in Aldbrough and York) seeds some of the poems, and in these Gilham skillfully avoids the nostalgia trap and looks with the eye of a curious observer. There are also poems in which he luxuriates in memories of his youth, the

plain beginnings,

knitting our youth

and again and again a valedictory sense that

life’s garment [is] at last complete,

a good job done.

The same could be said of this rich collection.

Hannah Stone

To buy a copy contact the author here

Hannah Stone is the author of Lodestone (Stairwell Books, 2016), Missing Miles (Indigo Dreams Publishing, 2017), Swn y Morloi (Maytree Press, 2019) and several collaborations, including Fit to Bust with Pamela Scobie (Runcible Spoon, 2020). She convenes the poets/composers forum for Leeds Leider, curates Nowt but Verse for Leeds Library, is poet theologian in Virtual Residence for Leeds Church Institute and editor of the literary journal Dream Catcher. Contact her on hannahstone14@hotmail.com for readings, workshops or book purchases.