Oz Hardwick, Wolf Planet,

The Hedgehog Poetry Press, 2020.

ISBN 978-1-913400-41-9. £5.99. 19 pp.

Oz Hardwick is well known for his creative work across fields as diverse as photography, music journalism and music performance, academic scholarship and creative writing. It is no surprise to find that this polymath of the artistic world has produced a metaphysical ‘yoking together’ of apparently disparate themes – here, astronauts and lycanthropes (to whom this elegant chapbook is dedicated).

Hardwick is prolific; 2018 saw the publication of Learning to Have Lost (which won him the 2019 Rubery Book Poetry award) and 2019 The Lithium Codex, also from Hedgehog Poetry Press (and reviewed earlier in The Lake), both of them prose poetry collections in Hardwick’s favoured chapbook length. The relative brevity of such publications makes for an intense, and highly focused, reading experience. This is repeated in Wolf Planet which evolves from the individually titled shorter prose poems of previous publications into a sustained tour de force of fantastical, trippy writing which is (to adopt a musical term) through composed.

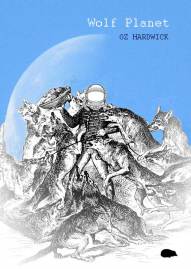

As might be expected from a medievalist, the past is precisely evoked; childhood memories of collecting ‘empty bottles for the threepenny deposits’ and ‘childish knuckleprints in polystyrene tiles’ jostle with apparently Victorian ‘places where there are still gas lamps and the warm shit from horse-drawn trams and drays.’ The nightmarish quality of the disassociation which can be experienced in ‘real life’ is also painfully convincing; ‘I check my pulse as if it belongs to someone else, write down a sequence of digits I don’t understand and will lose later on.’ The moon of the front cover is both the observed harvest moon of today and the location of the 1960s space race, the heady excitement of men on the moon, UFO sightings and the transitory pull of gravity.

The front cover of the pamphlet (crafted by the author) superimposes a forensically detailed line drawing of snarling wolves surrounding a figure(bizarrely dressed in space helmet and frogged jacket) onto a misty partial view of the moon. The visor of the helmet is blank, in an abdication of identity which resonates through this disturbingly gripping, darkly comic book, in which the eponymous Big Bad Wolf pops up like the baddie in the pantomime. By turn sinister, benign, world weary, the BBW grows into a complex and addictive raconteur, guide and alter ego. But we can never be sure where we are or where we will be led; ‘the data’s inconclusive, winking digits demanding caution while confirming the lack of alternatives.’ Likewise, the precise genre of the writing resists a simple interpretation; unlike previous chapbooks there are no titles to individual sections but there are narrative threads in this ‘space age folklore’ , to use the subtitle, suggestive of prose. Here is the best possible synthesis of prose and poetry, which teases its reader. The opening page acknowledges this process: ‘Sometimes the most important decisions come down to generic tropes and narratives expectations’ we are told, but such expectations are only established in order to be subverted.

That said, the narrator comes to an accommodation with the BBW – he is ‘not so big or bad, so I invite him round for tea every once in a while’ to discuss, among other topics, ‘a trend towards personal redemption and a wider morality in current comedy shows.’ Hardwick is open about living with mental health issues (The Lithium Codex records the impact on him of that particular ‘remedy’ for one of his diagnoses); we are left feeling that we may all have genetic threads of the wolfish within us, and can spend time coming to terms with those shadow selves within us. The story comes to an end of sorts, or at least pauses for breath as ‘the light fades and the howling starts, gathering darkness into a concert of freedom and need.’ I cannot be alone in eagerly awaiting the next instalment in the fairy story.

Hannah Stone

This pamphlet is available by subscription from The Hedgehog Poetry Press or direct from the author

Hannah Stone is the author of Lodestone (Stairwell Books, 2016), Missing Miles (Indigo Dream Publishing, 2017), Swn y Morloi (Maytree Press, 2019) and several collaborations, including Fit to Bust with Pamela Scobie (Runcible Spoon, 2020). She convenes the poets/composers forum for Leeds Lieder, curates Nowt but Verse for Leeds Library, is poet-theologian in Virtual Residence for Leeds Church Institute and editor of the literary journal Dream Catcher. Contact her on hannahstone14@hotmail.com for readings, workshops or book purchases.

Peter Ramos Lord Baltimore,

Ravenna Press, 2021.

ISBN: 978-1735113135. 75pp. $13.95.

Late in his new collection, Peter Ramos writes a poem to his daughter, from a writers’ retreat. “Father’s Day at the Artists’ Colony” necessarily takes a tone of experience in speaking to an innocent child. “Experience” boils down to “regret,” essentially, the searing memory of the false turns we take in life. The poem begins:

This morning’s nightmare

hangover dream:

head in a crevice, the whole body’s weight

dropped down, thud

repeating thud—such dull concussions

until the neck at last

begins to snap: lights out.

The old bulb’s blown.

The remorse, the contrition, so often the basis of nightmares, leaps out at you. Another resident, a woman in her forties, has fallen off the wagon, turned to the bottle, and then disappeared:

God knows

where to. And you—with time enough

to be brave, like your mother—can wait

to know. Dearest,

be aware…

So much of Lord Baltimore involves a kind of futility, living hand to mouth, questioning the validity of one’s own goals, the uncertainties that come with youth. Am I simply a fraud, after all? Peter Ramos takes us through his childhood and early adulthood in Baltimore, that city that Donald Trump loves to trash as some sort of third world shithole. In Ramos’ poems, it’s at once more boring than that, and even more “romantic” – at least in the sense of being the setting for the author’s “quest.” He remembers the dawning of his self-awareness, growing up and away from his family in “King Size,” from the first section, which covers his childhood.

Plump and wide, gigantic

sheet-cake with vanilla frosting!

Big enough for dad

and mom, even the kids.

We’d come between them. We’d sleep,

all of us dreaming, drifting

apart. One night my brother and I

opened our eyes and split. At dawn

our parents awoke, suddenly

strangers.

The second part deals with this alienation that comes with adolescence. It starts with the rebellion against his father, in “Immigrant Song,” (“I slam my bedroom door, drop the needle on Led Zeppelin and / turn the volume knob all the way. That’ll show him.”), proceeds through teenage years, the liberation offered by cars, and experiments with sex (“Both sixteen, we plan for this—a glaring Sunday afternoon. I / pick her up and we drive to the auto-tire plant, closed for the / day, park behind it, up against the barbed-wire fence, then slide / the front seats forward, get in the back to kiss and undress.”) It is precisely the boring, narrow-minded suburbia from which he is trying to escape. As he describes it in “American Pastoral”:

The neighborhood men

sprawl out in busted lawn chairs,

a stack of hollow cans glinting

in the sunset. They’re loud with hatred

for work, the economy, for the liberal

and Jew. The black kid, only fifteen,

watches warily from across the street…

At the heart of the collection, the third of the four parts, is the 17-page eponymous poem, “Lord Baltimore,” in which Ramos is an aspiring writer, a man in his twenties. It proceeds through a kind of aimless despair – snippets from “Everybody’s Talkin’,” Harry Nilsson’s theme song from Midnight Cowboy, provide a kind of background music (I’m goin’ where the sun keeps shinin’ through the pourin’ rain).

Here’s to you, Lord Baltimore, not Poe. I’m yours

truly, sunk, un-publishable, a mere scribbler

bon vivant, my glasses cracked & knocked

askew. By noon, I’m just another

dipshit local drunk.

Such despair! Crummy jobs, one at the Baltimore City Waste-Water Treatment Center (“or brick shithouse”), failing to make rent, having to move back home in the suburbs, as if in defeat – setback after setback while he pursues his vision of becoming a writer – make up the narrative momentum of this poem. Except for the few who find an audience almost instantly, what writer or poet hasn’t felt this insecurity, this lack of confidence? Ramos frequents many a legendary Baltimore watering hole in the Bolton Hill and Charles Village neighborhoods – Club Charles, The Mount Royal Tavern among them – engages in passionate but loveless sex, his typewriter his only true companion. To sum it all up, he asks himself:

What were you looking for?

That’s easy—love, but the only thing

you remember now was the last Friday morning

of winter months, going out for coffee, the hangover

still throbbing your skull and seeing on either side

of Saint Paul Street: evictions!

In the fourth and final part, Ramos, an English professor at Buffalo State College in New York, is now on firmer psychological ground (“Come Back, Pink Flash” begins: “Safe in middle-age….”), though as we’ve seen in his Father’s Day poem, still very much in touch with his more fragile ego: this is the future that may or may not await his daughter. It’s always nearby, too, beckoning like the seductive sirens in the poem, “Mall Flowers,” when memory comes crashing down on him:

To go back there, alien

again in the arcades—dark,

the low smoke lit by lighted screens

as we, black-eyed, watched

them drift away, the girls

with older boys who held

or rode them in Firebirds—

is to forget: we longed.

Still, it’s hell to descend.

If pushed or squeamish,

know this: come also boredom-speak….

Lord Baltimore is written in a vivid, urgent style that befits the story it tells, truly mesmerizing.

Charles Rammelkamp

To order this book click here

Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore, where he lives, and edits The Potomac, an online literary journal. http://thepotomacjournal.com. His photographs, poetry and fiction have appeared in many literary journals. His latest book is a collection of poems called Mata Hari: Eye of the Day (Apprentice House, Loyola University), and another poetry collection, American Zeitgeist, is forthcoming from Apprentice House.

Angela Readman Cooking with Marilyn, Blueprint Poetry, 2020.

ISBN 978-1-9162025-2-8.

Readman is established as a writer of poetry and short stories, her first collection of which, Don’t Try This at Home, won the Rubery Book Prize; her first full–length collection The Book of Tides was published by Nine Arches in 2016. Cooking with Marilyn is a slim, accessible assemblage of work about Marilyn Monroe, and brings together poems for the most part already published in journals. There is a sustained intensity to this chapbook, capturing the short life of extremes endured by its subject. Monroe’s dysfunctional childhood, her brief highly publicised marriages to famous men, her career as pin-up girl and actress, are captured as vignettes, or polaroid prints.

Appropriately, for a subject so much in the public eye, visual acuity dominates the verse, together with strongly sensual images. In ‘A Lake with the Name of a Girl’, ‘the night’s open mouth sucked at the lake’; elsewhere a discarded dress is a ‘puddle at my feet’; flour ‘mushrooming a nuclear cloud in your hair.’ ‘Nobody’s Perfect’ offers the strikingly resonant description of ‘Sunrise [as] a blond with her roots coming through.’

There is wit alongside insecurity in ‘Zoo’, ‘where all the leopards are women in coats known to change, and hyenas are spotted instantly.’

The self-consciousness and chronic insecurity of Monroe is vividly represented through the repeated invocation of emerging or transactional sexualisation associated with a woman at once glamourous and vulnerable. In ‘Rhone Island Street’ the young girl who spent her childhood shunted between family members and abusive foster carers ‘know[s] it’s time to be called woman’ even though her lips ‘haven’t yet learnt to be lips’. She watches a girl ‘about my age’ practising for adult life:

her eyes making a meal of a sleek man …

she toys with a bowl and spoon,

pulls a blanket of slow cream

over a bed of strawberries.

This makes us feel Monroe was doomed to her brief life of exploitation and self-medication with drugs, as if her gaze on adult life was focalised far too soon through the lens of sex. Some of the poems required a detailed knowledge of her biography. ‘The Scent of Mrs DiMaggio’s Bedroom’ is broken into nine verses, one for each of the months of her marriage to the former sportsman. Many refer to her films and other aspects of her career, and are effective at conveying the manipulation of Hollywood.’ Some Like it Not’ tells us ‘being so sweet isn’t as fun as it looks. She’s sick of spooning herself out. Filling cups nobody returns.’

For me the most accessible poems, and the ones where I felt Monroe’s inner strength alongside her fragility, were the ones about her childhood. You do not need to know much biographical detail to appreciate ‘Orphan’ with its terse lines:

in cloudy water, you saw your place. Soon,

you’d pack, for another foster home. Arriving

with the smile a nun taught, you climbed stairs

above a laundromat where all your kisses and prayers

tasted of bleach.

At their best these poems transcend tight tethering to a detailed cultural framework and instead simply invite empathy. I’ve sometimes debated with fellow poets whether any poetry can be universal in its appeal (whether this is desirable or not is another issue). The more verse focuses on and refers to specific subjects, the more it might deter or exclude those who don’t share that background knowledge or perspective. This is where craft comes in; the ability to use words to create their own layers of meaning. Whether or not you know the movies, you can recognise those dusky times of ‘the day being taken down one bulb/ at a time.’ For this ability to engage with a wider readership, I commend the book.

Hannah Stone

Copies of this pamphlet can be ordered from blueprintpoetry@gmail.com

Hannah Stone is the author of Lodestone (Stairwell Books, 2016), Missing Miles (Indigo Dream Publishing, 2017), Swn y Morloi (Maytree Press, 2019) and several collaborations, including Fit to Bust with Pamela Scobie (Runcible Spoon, 2020). She convenes the poets/composers forum for Leeds Lieder, curates Nowt but Verse for Leeds Library, is poet-theologian in Virtual Residence for Leeds Church Institute and editor of the literary journal Dream Catcher. Contact her on hannahstone14@hotmail.com for readings, workshops or book purchases.