Hannah Stone, The Invisible Worm,

Indigo Dreams Publishing, 2023.

ISBN: 978-1-912876-82-2. 51pp. £9.50.

The Invisible Worm is billed as ‘part threnody, part celebration of friendship’, written in memory of Stone’s friend Rosemary Mitchell, Professor of History at Leeds Trinity University, who died in 2021 of an aggressive cancer. The collection is divided into two parts: ‘The Invisible Worm’, which charts the course of Mitchell’s illness, her death and its aftermath; and ‘A Testament of Friendship’, which includes eulogies to Mitchell’s parents, Leslie Mitchell and Eileen Philippa Mitchell, who died respectively in 2014 and 2017, and poems that cover highlights of Stone’s friendship with Mitchell. There is also an addendum of two poems by Mitchell herself.

Hannah Stone is best known for her poem ‘Second Sleep’ which was selected by Carol Rumens as Guardian Poem of the Week in February 2023. It’s a superb, beautifully nuanced poem. There is nothing of this calibre in The Invisible Worm but perhaps that would not be appropriate for a collection of this kind where artistry might prove intrusive to the act of commemoration.

However, while most of the poems in ‘The Invisible Worm’ are restrained in this respect there are exceptions where the material is overworked. The starting point in ‘Short Changed’ is Mitchell’s sadly misguided belief that her initial cancer symptoms were due to ‘the change’. The subsequent wordplay on ‘change’ as in money seems forced, a series of Metaphysical conceits that militate against emotional engagement. Ward-round updates are characterised as ‘usury’ and tumours as having ‘embezzled your life’. Another example of this approach is ‘The Guard Dog of Ward 96’ where a health professional is cast as Cerberus. If like me you had forgotten the significance of this figure from Greek mythology, Cerberus was a three headed dog that guarded the entrance to Hades. The comparison is strained and draws attention to itself rather than successfully capturing an aspect of Mitchell’s time in hospital.

Fortunately, the majority of the poems are more subtle and more effective as fitting elegies to Mitchell’s memory, or rather as an expression of Stone’s grief for her friend. The bareness of the following stanza from ‘Hold Tight’ resonates all the more because it does not strain for effect:

Wanting occupation, I open

and close drawers; trot up

and down stairs with armfuls of clothes,

folded for the charity shop

This is a rite of passage that all of us in these circumstances have experienced, dealing with the quotidian business of the disposal of belongings, either during a terminal illness or after a death. At other times, Stone achieves a lyrical intensity which is unstilted, as for instance with ‘In Heaven’ when she revisits a wood where she and Mitchell had walked together the previous May:

Laved by overnight rain

the woods dissolve into birdsong,

explode in drifts of blue and white

where ransoms lace the river bank.

The pastoral setting here is beautifully realised.

In ‘A Testament of Friendship’, which comprises most of the second part of the collection, Stone achieves much more consistency than in ‘The Invisible Worm’ in terms of transcending the source material. These 4 poems are inspired by trips Stone took with Mitchell to various locations: Valetta, Rudston (associated with Winifred Holtby), Northumberland and Firenze (which references Keats). Appended to the sequence are ‘Tuscan Haiku’, a run of 16 haiku which are invested with occasional dry humour: ‘Holy Trinity/undergoing maintenance/ I have days like that’. Finally, there is the standalone ‘Evening Stroll from Gap Cottage’. The poem is in terza rima, the rhyme scheme devised by Dante for his Divine Comedy. The association seems fitting and Stone handles the difficult form adroitly, ending the collection on a high note with this strong poem. It is not surprising that it was shortlisted in the York Amnesty International competition on the theme of ‘Locked’ in 2021. ‘Tuscan Haiku’ too was previously validated, having been published in Coast to Coast to Coast, Issue 6, Summer 2019.

As a book overall I am not sure how wide an appeal The Invisible Worm possesses but certainly there are several poems included that would be enough to justify the cover price.

David Mark Williams

To order this book click here

David Mark Williams writes poetry and short fiction. He has two collections of poetry published: The Odd Sock Exchange (Cinnamon, 2015) and Papaya Fantasia (Hedgehog, 2018).

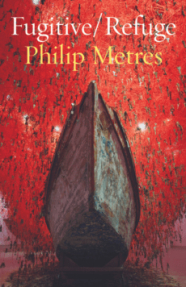

Philip Metres, Fugitive/Refuge,

Copper Canyon Press, 2024.

ISBN: 978-1-55659-669-8. 144pp. $22.00.

Taking on the themes of immigration and exile, the uprooted and homeless – the refugee, the “stranger in a strange land” – in sometimes painfully personal terms, Philip Metres’ new collection is vital and relevant, especially as we are confronted with the increasingly isolationist cruelty on the right.

At the heart of Fugitive/Refuge is the story of Metres’ own family, from his great-grandfather Iskandar ibn Mitri Abourjaili’s exile from Lebanon at the start

of the twentieth century, the family’s flight to Salina Cruz, Mexico, to their subsequent flight to the United States. Born in San Diego, Philip Metres grew up in Chicago and is currently a

poet and professor of English at John Carroll University in Cleveland, where he is also the Director of the Peace, Justice and Human Rights program. Piecing together his family’s history from

documents, old photographs, and the stories of his father, great aunts and uncles, Metres reminds us in a footnote to the poem, “(The Ballad of Skandar II)” – written in Arabic – “‘Once upon a

time,’ in Arabic folktales, translates as ‘there was and there was not.’ Maybe it happened, maybe it didn’t.” The broad outline of Metres’ own story, certainly, is true. Including a couple of poems

inspired by his daughter Leila, the story of the Metres family spans five generations.

Metres frames the story after the qasida, an ancient Arabic poetic form, a three-part thematic progression from nostalgic reflection, which Metres identifies as “fate” (the translation of the Arabic word Nasīb), to travel through the world (raḥīl) – a sort of exile – and finally the “return” – praise of the tribe (fakhr) or a ruler (madīḥ), satire about other tribes (hija) or some moral maxim (hikam). Fugitive/Refuge begins with a “Qasida for the End of Time” and a section setting up the terms of his personal refugee story, from a “Dramatis Personae” section in which he identifies the ancestors, from his great-grandfather on, and several poems including “Fleeing from Salina Cruz after the Murder” and “The Arab Crosses into Los Estados Unidos”; then the three-part structure defines the rest of the collection – Of Fate & Longing, Of Exile, and Of Return.

“Qasida for the End of Time” is in three parts, of course, and so represents a microcosm of the entire book’s arc. In “A Chronology of Roads,” the second (exile) part, which spans all time, from the biblical era through the present, Metres writes, “Once God

was mountain thunder, or drought, or floods

something to sacrifice a child to, the fist of justice

slowly opening. Then God was a flaming shrub, then

a tickle in your insomniac ear. Once forgetfulness

was waking hungover, alarmed, driving to a dying

factory in a Rust Belt town. Then it was running

past empty in the middle of winter, testing the limits

of emptiness.

The poem concludes with the return “At the Arab American Wedding,” where “we danced

dabke—clasped hands

with cousins we knew

or barely knew, arms braiding arms,

feet stepping as if into dark

lifting and dragged

back & forth

as if the foot were snagged

on a fit of remembering

Indeed, of

Fugitive/Refuge is all about memory, piecing together the fragments of history into a cohesive whole that explains but remains a mystery.

Metres employs a variety of forms throughout the collection,

weaving in Arabic words and script throughout. One form he uses several times is the “Arabic simultaneity,” which contains two voices, one reading from left to right, the other right to left, as both

Hebrew and Arabic are written. The penultimate poem in the collection, “You Have Come Upon People Who Are like Family and This Open Space” includes the verses echoing the title:

people upon come have you

family like are who

space open this

space this open

you welcome I that

away turn to

stay to wish you unless

Read those lines right to left to apprehend the longing, its

fulfillment in the sense of “return”.

Refugees often lose their names along the way. Skandar becomes Alejandro in Mexico, and Felipe becomes Philip, moving to the United States. “We Were Almost Meters” presents a facsimile of a Department of Labor document in which “Meters Felipe” is described as leaving Salina Cruz, in Oaxaca, Mexico, for Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1923. The “Meters” is crossed out and “Metres” penciled in. Think of all the stories of immigrants’ names being changed at Ellis Island. (The old joke about the Chinese laundry owner named Bernie Schwartz goes that after a Bernie Schwartz was registered and the official asked the next I line for his name, he’d responded “Sam Ting.” Hence his business, “Bernie Schwartz’s Chinese Laundry.” Ho ho.) As he writes in “Raise Your Glass”: “A toast to the migrants // the authors of movement / who write with their feet.”

A related issue is the homeless in our country. Metres’ work in the Peace, Justice and Human Rights program at John Carroll University brings him into touch with people in Cleveland who have slipped through the social services safety net. “Disparate Impacts” tells the story of Joseph Gaston, whose difficulties finding housing, with the laws and courts seemingly set up against him; it’s heartbreaking. “Upon Hearing of Plans to Remove the Gazebo” tells the story of Tamir Rice, the twelve-year old Black boy Cleveland police murdered for waving a toy gun. Similar to Joseph Gaston’s story, “The House of Refuge” tells the story of Christana Gamble, another Cleveland person whose struggles with homelessness are poignant and difficult. Both poems read as official transcripts.

As the title of this collection indicates, Philip Metres loves the sound of words and the rhyme of their meanings. Not surprising for a multilingual poet, of course, but his various takes on the meaning of “manifest” throughout, his teasing out of the thread of the Arabic word “jahash” in the poem titled “Ass,” and his poem, “Never Describe the Sky as Azure” which takes on the meaning and etymology of “lapis lazuli” (“migrating from Persia, / smuggled from Farsi”), all show a mind fixed on language, which is evident throughout the collection. This, too, is appropriate to the immigrant experience. “Song for Refugees” plays on “oud,” the Middle-eastern stringed instrument, beginning: “Ooze, oud” and weaving a dreamlike rhyme all the way through its four four-lined stanzas. Metres writes in “The New New Colossus,” alluding to the Statue of Liberty, “Her tongue tasting language after language.”

Fugitive/Refuge is a fascinating tapestry of personal experience, seemingly insurmountable human obstacles, and universal truths.

Charles Rammelkamp

To order this book click here

Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore, where he lives, and edits The Potomac, an online literary journal. http://thepotomacjournal.com. His photographs, poetry and fiction have appeared in many literary journals. His latest book is a collection of poems called Mata Hari: Eye of the Day (Apprentice House, Loyola University), and another poetry collection, American Zeitgeist, is forthcoming from Apprentice House.