Two reviews by Hannah Stone

Jean Atkin, High Nowhere,

Indigo Dreams Publishing, 2023.

ISBN 978-1-912876-80-8. 103pp. £11.00.

You won’t find ‘High Nowhere’ on any map, but you may locate it within your own heart, if you are the kind of soul who feels meshed with the natural world, and resonates with its music. Ostensibly, this collection from established poet Jean Atkin focuses on what she has ‘read’ from landscapes including her home ground of the Welsh borders and more especially Iceland, which she visited during the pandemic. But to describe this as nature poetry would do it a disservice. The black and white photos (taken by the poet herself) which adorn each of the sections (Brink, Spread, Source, High Nowhere, Fable, Path) comment wryly on the fragmentation of our lives and the escalating disappearance of parts of the world; the two of skeletal remains of birds are especially striking. They act as an aide memoire to where we, as a species, are heading.

It is a meaty collection, with a lot going on; not only the structuring into sections but the slightly gnomic use of italic lower case for titles of some poems; I pondered, but wasn’t sure, if put together these words created a secret poem of their own (wood, light, clocks, slick, north, melt, front, heart, path.)? There are also a number of ‘translations’, to do with the transformation of an elemental substance into something else: magma into scoria for example (and if you are unsure about these specifics, there are notes at the back to enlighten you).

The context in which the collection was written makes it almost impossible to avoid writing about the pandemic; compared to the later poems, I felt these added less that was ‘new’ about our individual and collective experience of living through the Anthropocene.

One of the four epigrams is a comment from Wendell Berry: ‘there are no sacred and unsacred places; there are only sacred and desecrated places.’ This to me provided the best map to the landscape Atkins writes. Sometimes there is elegiac lament; the ‘cryptic treehunter’ has had its habitats: ‘islanded by fire and blade and plough and profit’; on a volcanic beach (‘Vik’) she ‘ground [her] boots in raven sand’ and

… some mornings

are a smashed seabird and a gull-coloured sea.

Some mornings are hunters.

Sometimes there is a sense of fierce agency about the planet’s ability to fend off the human cuckoo, as a temporary irritation which has scant ability to hold its own against the elemental forces, such as constantly active volcanoes. Atkins loves personification; the eponymous Fagradalsfjall, spied on while in active phase, offers ‘here and there a vile red eye to wink the thinness of the crust’. A rainbow:

… grew and arched its back …

… I watched it shy like a horse, then fold

its legs, and lay down across the pale gold mountain (‘Blahnúkúr’)

(Oh I wish it had been lie not lay!)

I enjoyed the description of the ‘Death of an oil rig’; ‘Winner … towers over the lean cold fang of the cliff’, and ‘the thrashing rig’ is dragged ‘ … through shallows up the beach/a lurching fighting fish that bucks and groans.’

Even the use of Hawk, the ‘heavy-lifting ship’ used to shift the rig to where it is dismantled is seen as being in intimate relation to the rig: ‘… a couple, but a very temporary affair.’

Thus we are invited to participate in the death-throes of the civilization we take for granted; not merely as observers, but culpable participants. These two are interconnected, as the penultimate poem (path) spells out:

This tender ground is full of paths and graves.

The dead are always doing something new.

Meanwhile the living breathe the air. We eat the plants.

We love. We’ve work to do.

Atkins gives the last word to her pet cat, in a rare touch of levity, which nicely rounds off an intense journey.

To order this book click here

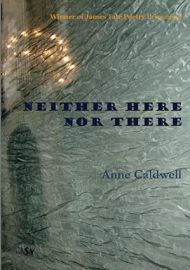

Anne Caldwell, Neither Here nor There, SurVision Books, 2024. ISBN 978-1912963478. 32pp. £6.99.

As she has gravitated increasingly towards writing prose poetry over lineated verse, Caldwell’s work has become increasingly surreal. Given the sustained quality of her writing, it is no surprise that Neither Here nor There was a James Tate Poetry Prize winner in 2023, a competition established to promote surreal poetry. This slim volume from innovative press SurVision is an engaging read.

There are some echoes of previous collections; the titular protagonist of her 2020 Valley Press Collection Alice and the North makes a cameo appearance, finding ‘life’s heat and joy’ and perpetual motion in ‘GlassBlower.’ And, as in much of her work to date, the physical and emotional landscape of the Pennines, its flora and fauna, run through the poems like the warp of a loom, offering stability to the weft of apparently random and diverse themes. The light over Saddleworth Moor is ‘forever rainsoaked’ (‘Red Tulips I’); time is measured by migrating birds: ‘here on the moors the curlews have returned; they’re nesting in the field above Top Brink.’ (Blue). Although the title of the collection plays on words associated metaphorically with location, there is for me (as a lover of similar landscapes) a very strong sense of place sustained in these poems, a real conviction that we are ‘here’, with the poet, looking through her eyes.

Lockdown makes an occasional appearance, as a manifestation of combined isolation and despair which is one of the emotional threads in these poems. In simple metaphors, Caldwell captures her own sense of the melancholy and its mirror image, the ‘thing with feathers’ (citing Emily Dickinson, in ‘Late Snow’). ‘Fallen’ and ‘Philomela’ bring in voices from familiar myths, subverted to displace expected narrative flow in lieu of immediate impressions, couched in mouth-watering language: ‘I thought of my father. He was one of life’s dreamers, one of Larkin’s lecturers, lispers, Losels, loblolly men.’ (‘Fallen’). Interspersed with the griefs and losses are outbursts of sheer exuberance: ‘For fuck’s sake, I am wide awake and kicking the start of the year into the long grass where it belongs’ (‘Not I’), not to mention the ‘nimble and giddy’ words that ‘wore dancing slippers made of silk’ when ‘the moon was up’ (‘Dancing Slippers’).

This collection is striking for its straightforward use of simple metaphor rather than simile, covering the whole gamut of sensory, emotional, and intellectual experiences; ‘Now is a copper saucepan, coated with olive oil, garlic just about to burn’ (‘Now’); ‘Today melody is a sparrowhawk, gliding above the heather.’ (Live Streaming Friday’). ‘For a while, Love was a ship marooned in ice.’(‘Late Snow’); ‘I am an egg with a shell so thin I could crack open under the kindest touch’ (‘The Shut Drawer’). And in ‘Seabed’: ‘Down here, your silence is a draft of cold Guinness, soothing a heart parched of tenderness or love.’ None of these conjure up obscure visions, but Caldwell manages to endow them with a sharp focus that invites the reader to look afresh at situations they thought they knew.

In ‘Love Poem’ the fauna image plays out in a more sustained way: ‘Your words at bats at night … they’re cave dwellers … roost for a while and fall head over heels when introduced to mine in late September.’ The lovers’ discourse is ‘sonic chatter’, a neat way of capturing the universality and particularity of romantic connection, but the surreal elements lift this above a conventional love poem; it is allusive and enticing rather than explicit.

In these perfectly crafted, always surprising, poems, Caldwell creates a sense of an interior world that avoids being self-reflective, but – rather shyly – invites you in.

To order this book click here

Hannah Stone is the author of Lodestone (Stairwell Books, 2016), Missing Miles (Indigo Dreams Publishing, 2017), Swn y Morloi (Maytree Press, 2019) and several collaborations, including Fit to Bust with Pamela Scobie (Runcible Spoon, 2020). She convenes the poets/composers forum for Leeds Leider, curates Nowt but Verse for Leeds Library, is poet theologian in Virtual Residence for Leeds Church Institute and editor of the literary journal Dream Catcher. Contact her on hannahstone14@hotmail.com for readings, workshops or book purchases.

Marsha de la O, Creature: Poems,

University of Pittsburgh Press, 2024.

ISBN: 978-0822967231. 72pp. $18.00.

In the eponymous poem, a juvenile Cooper’s hawk suddenly flies into the speaker’s home, turning tranquility into chaos. There she is, Marsha de la O writes, “battering her wings against / the baffling solidity of air.” The hawk is trapped “in a paroxysm of fear.” The speaker opens the windows, the double doors, disappears into the garage so as not to alarm the bird any further. The poem ends with the speaker “standing, shaking in the garage,

it must be a god I’m praying aloud to—the life

force

itself whose name is creature—saying, creature,

you can do it, you can find your way, creature.

Throughout this collection de la O writes about the fragility of nature and existence, all of us living creatures that make up the world, all of us making up that very life force.

The first poem in the book, “To Be Unprotected” (“Inside my

body, a hum or tremble / in a place where I keep fear”), is neatly balanced by the first poem of the third section, “The Day I Was Protected,” an homage to her father. whom she describes

throughout as a resourceful, creative craftsman. In “The Day I Was Protected” a crazy man offers to purchase his daughter, a very weird situation, and her father dismisses the man. It sounds bizarre,

but the piece ends, “I knew that day I had a home, the walls were made of glass, there was a horizon beyond.” (Earlier she describes her father as a glazier.) The idea is the stark vulnerability that

confronts us all and those welcome shields that provide comfort.

The poet writes lovingly about her father throughout the collection, beginning with his death in the second poem in, “My father died in the fullness of spring,” which

ends:

He didn’t acknowledge weakness. Or

complain.

But, over years, would not tend himself,

body and mind, a forgotten garden.

The image of the garden and, by extension, all of the natural world, is central to these vivid poems and the message of the buoyancy and strength of the spirit. The poem “Omens,” for instance, starts with a wildfire. “The hills went up like tinder / because they were tinder and spread the flames / everywhere.” The destruction is devastating, but “soon as ever grew a blanket of flowers, / mustard and wild carrot.” She goes on to show us the pair of crows whose nest, built in a pine, was likewise destroyed. She finds them now in a new nest in a scorched oak by an arroyo. The poem ends:

That’s where I saw the pair of crows

the male high in what’s left of the crown,

the female down below in shadow.

The male calling in hoarse, eager tones; the female silent.

“Late August Garden” is a poignant description of a garden on the wane as the season moves on. “I am least protected / when alone,” she writes, and then the poem turns to a memory of the poet’s mother, standing in her bedroom doorway.

Oh, Marsha, where did our lives go, she exclaimed.

It wasn’t long after her diagnosis.

Vines sprang

up

and clung to my walls,

and brambles covered my

eyes.

Why is my life over too,

I thought, why must I go with her?

Later, though, de la O presents a different vision of death and resilience in “Our Father Transfigured on His 91st Birthday,” when, shortly before his death, the speaker visits her father in the house he built high on a mountain. She has brought along a small grandchild. Her father, blind now, turns toward the child he cannot see. “The light breaks around her small body,

dazzles his skin, and under his skin blood threads like

red silk.

How are you, Kaitlyn, he croons. Are you fine? Can you say fine?

This tenderness we do not remember—it must have once fallen on us.

Such a subtle picture of rejuvenation and resilience. Such a sweet depiction of hope.

In poem after

poem, in the non-human world, the poet alludes to this enlightening transformation: “”Horses Resting” (“as though / Peace were part of the water table”): “A Field of Energy Knits You to Earth” (“We

all live in the gracious shadow / of one mother tree or another.”); “Helianthus” (“here’s gratitude / and dying every day, here’s waiting on the beloved.”); “Gravid and Amber “ (“I saw / life and

death take each other by the hand.”); “Prayer to Jacaranda” (“Leaf out, Artemis, let chlorophyll / harvest light”).

Marsha de la O also writes movingly about vulnerable girls, including what amounts to a lyrical defense of Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, who bravely came forward to shine a light on Brett (“I love beer”) Kavanaugh.

If we planted a tree for every

dead girl, we’d live in a forest.

“Girls in

Custody” is a tribute to a girl who was arrested, Russian style, for attending a rally for Trayvon Martin (“She wishes an old wish: don’t miss me.”).

These poems, and others with similar themes such as

“Paradise Motel,” “Afterward,” and “Water in Standing Pools” follow and contrast with “The Day I Was Protected.”

Marsha de la O’s poem about Gerard Manley Hopkins, “The Seer and the Seen” (“He died in a crumbling stone house in Dublin, his city of exile, / believing his poems

would never be seen”), also addresses the ambiguities of existence.

Say it’s mostly about loss then…

Except maybe he disappeared

into joy

in those weeks of fever…

Creature contains a number of ekphrastic poems, including “The Boy Who Went Looking,” “Sky with Four Suns” and “Leviathan.” The final poem in the collection, “Pelican Entangled in Kelp,”

based on Lynn Hanson’s painting, “Shroud,” captures all of Marsha de la O’s thematic threads in the picture of the seabird dying in the ocean but somehow, in death, as if lovingly embraced, leaving

an almost hopeful vision as

the fruit of her sex lifted, and

copper

ropes held him as in a hammock,

and in this way, the moon, urging

wave onto wave, rocked the dying

to shore where their great bodies,

stranded now, came to rest.

Creature: Poems is at once lyrical and thoughtful, meditative, brooding, and yet full of hopeful affirmation.

Charles Rammelkamp

Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore, where he lives, and edits The Potomac, an online literary journal. http://thepotomacjournal.com. His photographs, poetry and fiction have appeared in many literary journals. His latest book is a collection of poems called Mata Hari: Eye of the Day (Apprentice House, Loyola University), and another poetry collection, American Zeitgeist, is forthcoming from Apprentice House.