Eric Falci, The Value of Poetry,

Cambridge University Press, 2020.

ISBN-10: 1108429556. 170 pp. £ 19.99.

We’re all familiar with Auden’s contention that ‘poetry makes nothing happen’, but if we read on through his famous elegy he qualifies this statement in an interesting way: he suggests that poetry is ‘A way of happening, a mouth’. It’s this sense of poetry as a site of ongoing potential that underpins its value for Eric Falci. He’s interested in the complex relationships poetry has with the world, particularly its status as a site of ‘play’, with the capacity to expose ideological constraints and contradictions. Poetry is a different kind of discourse to, say, journalism, in that it’s not obliged to be communicative in the ordinary sense: it can be tricksy, ‘move laterally, by association and implication’ and is hence more adept at ‘presenting the fluxes, swerves, and fissures that characterise interiority, and of constructing varieties of subjective response to internal and external conditions’. In other words, it can behave irrationally without having to apologise to its dad, or its headmaster, or its editor. It may not be able to subvert ideology in a material sense, or exist beyond it, but it can make us aware of it, and, in Falci’s words, ‘suggest modes of individual and social relation that cut against the prevailing ideologies of the present’.

The first chapter explores this notion of play with reference to works like Jen Hadfield’s Nigh-No-Place (2008), and Harryette Mullen’s Sleeping With the Dictionary (2002); while the former invents meanings for obscure words, the latter, in poems such as ‘Any Lit’, creates variations of phrases around an inherited verbal formula; procedural and conceptual poetry of this kind reveals the instability of language and undermines our assumptions about how we relate to it. Wordsworth liked to think of poetry as ‘emotion recollected in tranquility’, while for John Stuart Mill it embodied ‘itself in symbols which are the nearest representation of feeling [...] in the poet’s mind’, but while such assumptions are ‘still with us’ they are clearly challenged by such ‘lexical games and sonic manipulations’.

In the second chapter Falci takes on the question of the ‘I’ and how poems can ‘represent the ways in which personas are embedded in the world’, with some deft readings of poems by Jorie Graham, Roy Fisher, Layli Long Soldier, and Claudia Rankine. In the latter’s Citizen: An American Lyric (2014), for instance, he shows how the author manipulates the reader’s relationship with the ‘you’ pronoun, problematising the possibility of easy identification either with the protagonist, or the racist perspectives also associated with that pronoun throughout the course of the text; in this way Rankine ‘forces a reader to continually understand the specifics of her or his own racial and social position’.

The third chapter deals with how poems create spaces for original thought and emotion: ‘how are thinking and feeling intertwined within poems’? Falci shapes a methodology via Charles Altieri’s work on aesthetics, Paul Valery’s comments on emotion in poetry, and G. Gabrielle Starr’s research into the relationship between art and neuroscience, and offers a convincing reading of Tracy K. Smith’s ‘Mangoes’, showing the symbolic function of the cigarette in the poem: it becomes a generative image that ‘works across the sensorium: a smell and slight haze at the beginning, a visible and tangible remainder toward the end’ and manages ‘to link the texts narrative course and affective substance to the reader’s own bodily and cognitive activities’ - in other words Smith creates ‘an image to think with’: to enjoy at the level of the senses, and the intellect.

While some poets favour cohesion and unity in their work, others are drawn to experimentation. As Falci associates value with poetry’s transgressive potential (as opposed to, dare I say, it’s potential to entertain us), he spends a good deal of time discussing the avant garde: the kind of texts most of us tend to know about rather than read, such as Tongo Eisen-Martin’s Heaven Is All Goodbyes (2017) and Lisa Robertson’s ‘post-Language’ poetry; however, his readings are always accessible and germane to the central thesis, which develops clearly as the book unfolds. In the final chapters he addresses the themes of ‘recollection’ and the environment by way of, among other poems, the highly experimental Zong! (2008) by M. NourbeSe Philip, and Stephanie Strickland and Nick Montford’s Sea and Spar Between (2010). The former constructs a fractured ‘hauntalogical’ account of mass murder on an eighteenth century slave ship, while the latter creates a (literally) unreadable computer-generated poem with a potential 900 trillion lines. While Philip operates in a paradoxical realm where we are compelled to retrieve an irretrievable past, Strickland and Nick Montford position us in relation to an unfathomable future, meant to parallel our relationship to geological time and our unknowable impact on a planet we can never fully comprehend. Both poems illustrate what Falci sees as the value of poetry as,

something of a counterforce. It appears both as emerging as residual, it can gesture toward that which cannot yet be seen or is seen no more, and it can bring to the surface some aspect of what has been overlooked.

Flaci’s argument is slick and lucid throughout, and the book offers valuable insights into how high culture poetry works - or is working - in the modern world, and how we might approach it as readers. It may ‘make nothing happen’, but it gives us deeper insights into what is happening and what we might do about it.

Paul McDonald

To order this book click here

Paul McDonald taught at the University of Wolverhampton for twenty five years, where he ran the Creative Writing Programme. He took early retirement in 2020 to write full time. He is the author of twenty books, which cover fiction, poetry, and scholarship. His work has won a number of prizes including the Ottakars/Faber and Faber Poetry Competition, The John Clare Poetry Prize, and the Sentinel Poetry Prize. His most recent book is Allen Ginsberg: Cosmopolitan Comic (2020).

Ruth Aylett, Pretty in Pink, 2021, 4Word Press. ISBN 978-2-490653-07-3. £5.99.

Aylett’s 2016 pamphlet collaboration, Handfast (with Beth McDonough) showed us a poet well skilled at revealing the ‘skull beneath the bone’ to quote John Webster (and T S Eliot); she does not shy away from shining a light on the disturbing events and subjects in the lives of women and men, which society may choose to conceal or ignore.

In this newly released first solo pamphlet, Aylett’s strongly political voice shapes poems about ‘becoming women,’ the types of transformation and adaptation we engage in within our own contexts. This portrait gallery includes female role models such as Rosa Luxemburg and Norma Jean, and a wide range of anonymous women, each of whom processes and sometimes triumphs over the challenges afflicting what de Beauvoir calls ‘the second sex.’ Aylett’s professional work as an academic in the field of computer science is glimpsed in the detailed choice of image and description in these poems, which are engagingly full of human warmth. Here are poems which refute the pigeon-holing of gender identities, the pressures of contemporary society’s premature and excessive sexualisation of girls, exposing the dangerous untruth of ‘selfies’ and the pressures to conform on a Saturday afternoon when ‘…The friends/she doesn’t have will meet in town,/giggle about boys, go shopping,/try out the lipstick testers.’ (‘Billy-no-mates.’)

‘Primes of life’ is a clever ironic listing of female behaviours and attitudes captured in snapshots of particular ages; despite the mother’s feminist ideals, the small daughter is ‘desperate/for a pink princess costume/and a dolls’ make-up kit.’ (Deprived of Barbie dolls by my well-meaning mother, this resonated with me).

‘Titration’ is an appallingly understated account of sexual assault, using the image of the ‘drop at a time from the burette’ to explain why we may accept rather than fight against what is expected of us as women, the repeated ‘Because …’ making excuses for the behaviour of others within a patriarchal society. The absence of graphic detail is telling.

There is great tenderness in ‘Iseult’s complaint’ where Aylett adds her own touch to the Wagner original, inviting us to question ‘…What’s the music/for habit and comfort, shopping together,/arms round shoulders, the times I cut his hair?’ The honesty and lack of sentimentality in this poem, as in so many others, makes the book a very nourishing and satisfying read, bearing out Aylett’s claim in her preface that ‘There’s anger and sorrow in my poems, but hope as well.’ Yes, this is so, and it makes the book not a threnody but a beacon.

Hannah Stone

To order this book click here

Hannah Stone is the author of Lodestone (Stairwell Books, 2016), Missing Miles (Indigo Dream Publishing, 2017), Swn y Morloi (Maytree Press, 2019) and several collaborations, including Fit to Bust with Pamela Scobie (Runcible Spoon, 2020). She convenes the poets/composers forum for Leeds Lieder, curates Nowt but Verse for Leeds Library, is poet-theologian in Virtual Residence for Leeds Church Institute and editor of the literary journal Dream Catcher. Contact her on hannahstone14@hotmail.com for readings, workshops or book purchases.

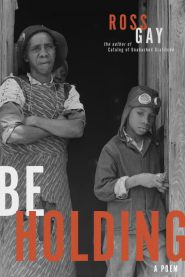

Ross Gay, Be Holding,

University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020.

ISBN: 978-0822966234. 120pp. $17.00.

Toward the end of this remarkable book-length poem, Ross Gay writes:

talking about

the practice

of the beholden,

a practice

of being beholden,

talking about

how might I hold

my beholden out to you

and you hold yours out to me,

how do we be holding each other,

how do we be

beholden to each other,

which is really to say,

“how do we be…”

The epigraph to Be Holding comes from Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake: On Blackness and Being: “…to be held. To behold.” In short, the thrust of this work is ultimately an attitude of gratitude, but along the way it’s also a lovesong to Julius (“Doctor J”) Erving, a deep meditation on being Black in America, a philosophical consideration of his own family – to all of whom Gay feels beholden – and a general groping toward what it means to be alive.

The poem begins with Gay watching a YouTube video of Game 4 of the 1980 NBA finals between the Philadelphia 76ers and the Los Angeles Lakers, in which Dr. J executed his legendary baseline move, a behind-the-board reverse layup, in which he seems to defy gravity. (“Flight” is a recurring metaphor in Be Holding.) Erving’s leaping ability was breathtaking. He was known for slam-dunking from the free-throw line. Gay poetically analyzes the play, considering the Laker defenders guarding Erving, the journeyman Mark Landsberger and the Hall-of-Famer Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Laker Jamaal Wilkes, known as “Silk.” (“among the finest basketball nicknames, implying an ease and fluidity of movement”).

It is 1:48 AM, April 4, 2015, when Gay obsessively watches the play again and again. As the poem progresses, he gives us a time check again at 2:26, 2:59, 3:11, 3:33, 4:56…In other words, he spends the whole night considering his themes, which leap off the page the way Dr. J leaps to the basket.

Written in short, two-line stanzas, the narrative free-associates with its themes. At one point he finds himself “treading water / in a college gallery” looking at photography exhibits. The function of the camera in seeing, “objectively” capturing, is a recurring thought. Between the famous image of a Viet Cong colonel being publicly executed and a naked child fleeing “the wreckage of her own napalmed skin” is another Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph of a Black woman and child falling from a collapsed fire escape in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston, in 1976. Captioned “Marlborough Street Fire,” it shows two people free-falling.

the black people falling forever

framed on the pristine white wall

becomes itself

a war photograph

“I, too, am a docent / in the museum of black pain,” Gay writes, and this idea succinctly expresses another his major themes, the suffering of Black people in America. Gay later considers a photograph of the little girl, Tiare Jones, who survived the fall when she landed on her godmother’s body “pointing and smiling at a photograph of herself / forever falling to her death.”

A little past midway through Be Holding,

I found myself looking through the WPA agriculture photos

at the Library of Congress

for my great-grandfather

as a young man, a sharecropper in Osceola, Arkansas

In his hands he holds a photograph of two Black people, a woman and a boy, likewise poor sharecroppers. This photograph is the cover of Be Holding. (Five photographs appear throughout the book, two angles of Dr. J’s baseline move among them.) Gay reflects on “the looking / this camera wants to do // to her boy / capture him.”

Thus, the function of photographic “evidence” is another important theme of this book. What does the act of photographing say about the “looker”? What does it say about the “looked upon”?

The final photograph, several pages before the poem ends, shows two young Black women, big smiles on their faces, walking toward the photographer. Taken by Carrie May Weems, its actual title is Welcome Home, but Gay writes:

a good title for this photo,

as though running down a great staircase made of air with joy

Gay writes about his mother, a White woman, staring down another White woman in the checkout line of a grocery store in Painesville, Ohio, whose look says to his mother, that brown child is not yours. His mother, “seeing / the not seeing” confronts the gawking woman,

and, in a voice

approaching the Luciferian,

counseled,

“Yes they’re mine

and I have the stretch marks to prove it”

Coming back to the woman and the boy in the cover photograph, Gay, “now holding my breath” (Breathing is an important, almost yogic instruction throughout Be Holding. Indeed, the final line of the poem is “we breathe”) asks,

how do we be

holding the child

so broken are we

by the breaking

and the looking

how do we be

holding each other

And thus, roughly three-quarters of the way through the poem, we begin the “descent” from the “flight” of imagination, so like the “flight” of Dr. J’s leap, a potent metaphor; but not before considering his dad.

and you’re goddamned right

I’m going to bring my father

into this poem

that’s just how it goes

The poem comes to an end with a final consideration of Dr. J’s baseline move. We don’t get a time-check after 4:56, but something tells me the sun is up:

after all that flying

he falls,

as the ball kisses the window

and drops through the net

Be Holding is at once an astounding tour de force and a provocative meditation on suffering and jubilation. As Gay paraphrases Amiri Baraka in his Acknowledgments, “The preparation for pain is minimal. For joy, a lifetime.”

Charles Rammelkamp

To order this book click here

Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore, where he lives, and edits The Potomac, an online literary journal. http://thepotomacjournal.com. His photographs, poetry and fiction have appeared in many literary journals. His latest book is a collection of poems called Mata Hari: Eye of the Day (Apprentice House, Loyola University), and another poetry collection, American Zeitgeist, is forthcoming from Apprentice House.