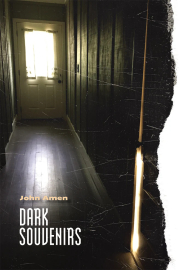

John Amen, Dark Souvenirs, NYQ Books, 2024. ISBN: 978-1630451080, $18.95, 88pp.

In the poem, “First Date,”

recounting how “I took a deep breath, pulled the pin, /

lobbed an I love you,” hoping the girl would “toss

that beautiful grenade back” in his direction, John Amen mines his youth for the emotional impact of the tense encounters, expressing it in the violent imagery of weapons of war. The poem

ends:

—don’t misunderstand me, I’m not

giving you a story. I’m trying to work

my way out of one.

Memory haunts Amen throughout this beautiful, meditative collection, as he tries to make sense out of all the suffering and violence and death, all of it freighted with heavy emotion, to work his way out of the story, as if defying Fate in an ancient Greek myth. Principally, it is the suicide of his uncle, Richard Sassoon, to whom the book is dedicated, that preoccupies him most, its irrevocable facticity. Try as you might to unthink it, it’s still always going to be there. Indeed, memory breeds regret. In the poem, “Two Years,” he writes:

two years gone like a skid on the highway,

sky & sky like an empty plate.

I should have tried harder.

Tried harder – as if he could have changed the outcome. The poem that precedes “Two Years” is, in fact, titled “Regrets.” It begins “I snatched the bottle from his hand / three weeks before he bought the gun.” Richard was a musician, a trumpet player (“He left me his demos”). The poem ends on this note of regret:

All summer I’ve wandered the heroin streets,

visiting every pawn shop in town,

hoping to reclaim that hand-me-down horn

he hadn’t played in years.

The poet certainly feels as though he let his uncle down, and this may be the real story he is trying to work his way out of, the mythos of family, how it controls us more than we like to admit. “The world / has always been broken or breaking,” he writes in “Ode to Country Music.” Indeed, music is a potent theme in Dark Souvenirs. “The Music at Hand” is about another (or the same?) Richard, who dies from an OD. Here Amen confesses, “I’m spelled by ghosts, they huddle in the shadows, / voices slurring on repeat, as if begging to be heard.” Elsewhere, in “Toward a Genealogy,” he observes that “beauty is horror’s common-law bride.” Families are so full of dark secrets.

Amen ponders his family, mother, father, his maternal grandparents who escaped the Holocaust, coming to America after having spent time in a concentration camp, arms tattooed.

There are questions I never posed,

& now there’s no one to ask,

that line of Jews reborn in America,

my American Jews,

buried in Christian ground.

His parents? The very first poem is called “Family Systems” and hints at this large family narrative that can dominate individual lives. “He should’ve

been the world’s youngest maestro

but spent his years hiding in the valves

of a westside trumpet, blowing sparks

but no music…

Is this Richard? It sounds like it, but later in the poem Amen mentions his brother’s funeral.

Hope can nail your feet to a burning floor,

grief can smoke the dirt under your shoes.

A month after my brother’s funeral—

spackled sky, red blooms on the gardenia—

I could hear my father grinding his teeth

from across the room. My mother stared

out a window…

Indeed, the scenes in Amen’s poems are surreal, dreamlike, as the Richards seem to multiply, become ghosts. “After Your Memorial” begins, “You rang my doorbell. I pretended / I wasn’t at home, crouched in stillness.” The nightmare continues. “Monday you returned. Tuesday, again. / Wednesday I answered, the revolving dream.” And then, significantly, “I held your trumpet toward you.” Who is this ghost?

In “Foster,” “Black Richard and pale I spent our sugar years / stomping through woods in search of a devil.” Richard seems to be a sort of Robert Johnson avatar here, the gifted musician selling his soul to the devil. Or not. But he’s all over the place, isn’t he? In “Breathless, “Richard rented a Corolla, blitzed the highway / from Brooklyn to Beaufort.” In “The 49 Days” the speaker seems to be Richard:

My cell rang in the afternoon.

My friend couldn’t shake his dream,

sitting across from me in a Sunken City café.

I tried to bring you back, he explained,

his voice disappearing in the ether.

Richard! Richard! he yelled into the phone,

the future fluttered in my throat.

In “No Longer July” we seem to come upon Richard’s body being discovered by the authorities, after he’s shot himself.

Detective Ana Garcia’s voicemail

splits the airwaves, how she unscrewed the door from its hinges,

boring her flashlight into a curtained room

–Richard slumped in his chair,

a scarecrow with a postcard lacquered to his chest.

If you hear Walt Whitman in this verse, you’re not alone! I think of those lines from Leaves of Grass: “Unscrew the locks from the doors! / Unscrew the doors themselves from their jambs!”

In “Remembering Richard,” he’s an itinerant photographer in the American west, the narrator his assistant. “I wake & slumber & wake again haunted / by the fact some capricious dawn the waking simply ends.” In “Crossroads” –shades of Robert Johnson again! – “Richard married & divorced three times, / stalked a teacher in Memphis.”

The last time we see Richard is in the final poem, “Impermanence,” and it feels like some sort of possible resolution: “Richie finally gets his ‘69 Corvette, / cruises uptown Bardo with big cash.” The Bardo! In a Tibetan tradition, the Bardo is the state of existence intermediate between two lives on earth. George Saunders’ Lincoln in the Bardo may have introduced the concept to a wider audience. One of the poems in Dark Souvenirs, indeed, is called “Bardo,” a short prose poem (for David) that reads:

I could see my son talking to himself, shadow-boxing his diagnosis. I remember wearing a hat made of smoke. What hurts is I left the ones I love wondering in the leaves, it wasn’t entirely by choice, I barely remember that carefree bullet.

There is more about his family, mother, father, siblings, the Jewish grandparents. In “Interdependence Day” he writes:

My grandfather’s sister died in a concentration camp in ‘44.

My mother says that most meals the ghost woman sat grimly at their table,

flashing her tattooed arm as often as she could.

Indeed, how the past haunts us daily. There’s no escaping it. But if there’s any consolation, early on Amen appears to recognize the absurdity and to come to terms with it. As he writes in “Homecoming,” the eighth of the sixty poems in Dark Souvenirs:

Blame, I’ve learned, is another diamond

that has to be given back to the earth,

left where you found it, white petals

shimmering in the dark.

Dark Souvenirs is riveting poetry, full of startling images and phrasing that take you back to Allen Ginsberg. The language reflects John Amen’s own musicality as well.

Charles Rammelkamp

To order this book click here

Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books. His latest collection is The Trapeze Of Your Flesh (BlazeVOX Books).