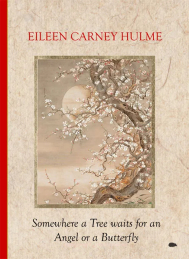

Eileen Carney Hulme,

Somewhere a Tree waits for an Angel or a Butterfly,

The Hedgehog Press, 2024,

ISBN: 978-1-916830-18-9, 24pp, £9.99

A new book by Eileen Carney Hulme is something to be celebrated not only because she is a poet always worth reading but also because her previous collection, The Stone Messenger from Indigo Dreams, appeared nine years ago and it has been a long wait. While in the intervening time she has remained active, winning prizes and gaining appearances in anthologies and magazines, for her fans there is nothing to touch a new collection from her.

What is striking about this small pamphlet even before you look inside is how beautifully it is produced, a testament to the high production standards of Hedgehog Press. It is a work of art in itself. The cover image, ‘Plum Blossoms in Moonlight’, a painting by the 18th century Chinese artist, So Shizan is both an enticement to open the book and a perfect accompaniment to the exquisite work inside .

The title poem is a good example of Hulme’s skill as a poet. For one thing it fairly fizzes with expressionistic flourishes. These are the opening lines:

I reach inside my heart, remove

a handful of leaves

This is as visceral as a painting by Frieda Kahlo. The last two lines are invested with a similar intensity:

My back to the bark I’m shaped

like loss, each little scar longing for wings.

What reinforces the striking imagery here is the internal half- rhyming (‘back’, ‘bark’, ‘scar’) which echoes ‘heart’ in the first line. Such effects point to a poem that is carefully woven. This is true of all the poems included here but how they are constructed is so subtle the effect is not forced. Unless one reads with an eye for technique her technical skills are not foregrounded but the impact is nevertheless undeniable. Such characteristics define her as a lyrical poet.

While each poem in the collection can be enjoyed on an individual basis, what adds cohesion to the book as a whole is the sense of an implied narrative, with each poem functioning as a scene or chapter. The narrative is focused entirely on two people caught up in a passionate love affair which sadly does not last. While this loss informs the story it is also invested with the heady euphoria of being in love.

Underpinning the narrative is a marked sense of location, primarily the seashore, which has a symbolic resonance too. The two people concerned seem literally on the edge of things. Their interaction is ‘shaped by beach walks’, their ‘small lives sea-tinged’ while the imminent dissolution of their relationship is heralded as a storm ‘holding itself/out at sea.’

These two aspects of story and setting endow the book with the impact of a film. Indeed all the elements are there for an arresting short movie with the text of the poems providing dialogue, shooting script and voice-over narrative.

I have referred earlier to the way individual poems are carefully crafted but this is true of the book as a whole. An example of this is the parallelism between the opening line of the first poem, ‘I want the wind, wild’, and the opening line of the last poem, ‘From a dream, confusion’. In the first example the comma is not required grammatically but forces the reader to pause. This is echoed by the second example where the comma is required both grammatically and semantically to ensure the correct reading but with similar effect: the emphasis falls on ‘wild’ and ‘confusion’. It is formalist elements like this that make Somewhere a Tree… so satisfying on an aesthetic level.

Much of the book proves resistant to simplistic explication. This is not because the poems are inaccessible, quite the contrary: Hulme’s style is lucid, one might say luminescent. What makes her work difficult to paraphrase is the delicacy of the execution, a content that hints rather than reveals. Hulme never has recourse to simply spelling something out, favouring suggestion and ellipsis.

However, while the poems are intensely lyrical she does not entirely ignore the more commonplace aspects of life. One notable example occurs in ‘Illusions’, which opens with a very down to earth issue: ‘I never quite managed to remove/that red wine spot from/my white linen dress, perhaps/I didn’t try hard enough.’ The risk with this kind of observation is descending into bathos. What elevates these lines is their symbolic weight. The stained dress is a metonym for the relationship and its aftermath. Furthermore red functions as a motif along with blue, like pure points of colour in a painting: ‘the blur hour flirts/a lust for colour/a before or after red’. These notations of the commonplace also underpin the narrative. These are two people in a realistic setting. When setting and lyrical expression combine the result is sublime poetry which we find in such lines as the following from ‘When You Wake’, the final poem in the book:

Dust motes hover in the half

light and you move to the cold

side as the house settles itself

around you and the often heard

creak in the hall breathes out.

Hulme creates a scene here that is atmospheric and disturbing, a perfect blending of vernacular and enriched language.

Hulme holds a unique place in the poetry world. She may not be as well-known as she should be but there is no other poet I know of like her, possessing a voice that is both instantly recognisable and of consistent quality. With Somewhere a Tree she consolidates her reputation as a fine lyrical poet. I fervently hope that we do not have to wait another nine years for her next book.

David Mark Williams

To order this book click here

David Mark Williams writes poetry and short fiction. He has two collections of poetry published: The Odd Sock Exchange (Cinnamon, 2015) and Papaya Fantasia (Hedgehog, 2018).

Dennis Hinrichsen,

Dominion and Selected Poems,

Green Linden Press, 2024,

ISBN: 978-1-961834-02-6, $20.00, 300pp

Dennis Hinrichsen begins the first of his new Dominion poems, “[mosaic] [with Henry David Thoreau and a Glove]”:

I am still a brain

with fire in it—all

these poetries inside

me crying out at once—

it matters more

these days as boon companions die—wind

blasting them

to papery smithereens—

I am voiceover now

for doom….

It’s an elegy [duh] – but with such personal reflection, it takes you back to the beginning of the book, Hinrichsen’s early career as a poet, in which in a similarly elegiac tone he reflects on the diminishment of his grandparents. Dominion is a volume of new and selected poetry, the new poems at the end, selections from ten previous books preceding in more or less chronological order. The collection starts with poems from the 2000 book, Detail from The Garden of Earthly Delights. Hinrichsen writes with poignance about his grandfather’s “withering brain” in the title poem, his grandmother’s decline in “The Hundred Thousand Lines Ending in Haiku” (“Sometimes I think the misery // is just some small nick inside the cellwork”):

Three days I’ve tried to

startle her

with memory, the purple martins

in their two-storied home, the Roosevelt dimes

all fled

to some afterlife…

Another new piece, the prose poem “[lyricism] [with Koi and My Voice on Speaker]” starts: “…meanwhile Parkinson’s is eroding a friend’s body—but not his mind so he is a kind of pilot in a plane with its engines on fire living by protocols and long naps….” Hinrichsen does not flinch from the grim realities, but there’s a kind of dark humor at work in his poetry, too. You see it in the titles. Among the new poems are “[On a Phone Call with Dementia] [and a Pot of Honey],” “[dominion] [Dream in which My Father Comes Back as Dr. No],” “[lyricism] [Louie Louie Me Gotta Go Now].” How can you not smile, even as you acknowledge the underlying horror?

The grim reality underlying “[Louie Louie Me Gotta Go Now]” is that friend with Parkinson’s. The poet and friend are walking around Spy Pond in Arlington, Massachusetts.

Lyrics that once bound with exquisite specificity

to our boy-child minds

reduced to chorus—broken

down creole—

he feels like oracle now—

so I pose questions—Do you fear Death?—No—

Is Sadness

truly immeasurable?—

Dominion and Selected Poems amounts to “Dennis Hinrichsen’s Greatest Hits,” selections from forty years and a dozen books, and this may be an appropriate alternative title, since so many of Hinrichsen’s poems, such as “[Louie Louie],” refer to popular songs. “Radio Cash,” from Rip-tooth alludes to Johnny’s “Ring of Fire”; “Death or Glory” from Electrocution, A Partial History channels the Clash’s song from London Calling; “[G-l-o-r-i-a] [Garage Band Take] [w/Tabs],” from This Is Where I Live I Have Nowhere Else to Go is another, and from Schema Geometrica, “[Anasazi Love Song] /w/Glen Campbell]” (epigraph: “Galveston, oh Galveston / I am so afraid of dying”), “[scansione] [David w/the Head of Goliath 1610] [Feat. Daft Punk & a Camaro]” (“Hours of funk or old school Motown on the headphones”), “[To Nicanor Parra at the Edge of Time] [w/Scotty Moore on Guitar] (“O Nicanor Parra // don’t let me go down like Elvis….”).” From his most recent collection, Flesh-plastique, there’s “[Self-portrait at 45 RPMs]” (“even then you were playlist // black disks slotted building perfect sets // back of your parents’ room because that’s where the stereo was…”), “[Waiting for the End of the World with Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass],” “[Despair in Open D] [with Gerard Manley Hopkins on Tom-toms] [and a Dead Flamingo].” “Baptism,” from Skin Music starts,

I held my breath a long time before I let the drowning

take over.

And then I was stood up, was put upon.

Larynx like a great cup wrapped in muscle

held to the light.

Jesus yip and howl.

Pre-Janis, pre-James Brown.

More pop than anything.

Beatle-esque, Mersey Beat.

The preacher’s hands still snorkeling my mouth.

White gown heavy and gelatinous with holy tap water.

It would take a long time before the howl

would cure

into something rawer, more sexual.

Wilson Picket’s midnight hour, Sam and Dave,

The Four Tops….

Music is a background to so much that is painful, troubling, like the end of his first marriage, when his wife tells him she is in love with another woman. Alluding to the LPs he has stacked in his study, the poet writes, in “Death or Glory,” “When my

wife finally tells me she’s a lesbian, I listen to

them again and think glory, glory, glory, the

wires frayed so one speaker phases in and

out like dying consciousness. Strummer’s

howl smothered near the jewel of the needle.

In another poem, “Queer Theory,” he writes sympathetically about his wife, her religious indoctrination as a child, that she was

pressed so far down

into the grain of a pew

it would take her

nearly half

her life—

*

and her mother’s death—before

she took

my hand and put it down. Our

daughter was in the other room—

we were

whispering—our words

were knives.

“The child hung between us like a / shared guitar,” he also writes in “Death or Glory.”

In “[schema geometrica] [w/CROCODILE],” when he becomes aware that his daughter is likewise queer, he writes:

& so I went queer // I liked Alyssa better

than Shannen // ate Buffy lore // adored Fiona //

—O choking ethos // tying down ethos // sharpened

pencils thrown at the head she lived in some days

until her anger was companionless & I was its echo //

how once to kill a summer afternoon we chalked a crocodile

in the driveway // measured tip of snot to crushing tail //

salt water gullet built to size // & then we laid down in it—

creeped ourselves with fear—until we were

hilarious again // undevoured

In one of the new poems, “[lyricism] [with Whiskey and a Windshield],” in which the poet is driving a car and observing a homeless man shambling along, singing to himself, Hinrichsen writes,

I have an imagination and a heated seat—

forget

I too am just another needle stuck in a groove—

black vinyl disc of city—

old school longing—

Indeed, life is a phonograph record that just keeps spinning round, as we pine, stew in our regrets, until one day it doesn’t spin any longer.

From the start, Dennis Hinrichsen has been focused not only on the images and ideas of his poems, their collision and contiguity – Horace and Catullus are comfortable on a farm in Iowa, Walt Whitman on the ward of a hospital, patients carted to X-rays and chemo, Caravaggio and muscle cars – but the very way they appear on the page, like an artist does his canvas. Three-line stanzas of various length and juxtaposition are all over Cage of Water, Kurosawa’s Dog, longer verses snaking around the pages of Skin Music and others, like “[Becoming Zero]” from Flesh-plastique. But punctuation, too, increasingly comes into play from around This Is Where I Live I Have Nowhere Else to Go and [q / lear] and in subsequent books, bracketed words, Dickinsonian dashes, and double slashes (//), and other diacritical marks, not so much affecting pronunciation but informing the contrast and continuity of ideas and figures. The brackets are unique, genius; they have the effect of isolating and emphasizing words, and in their juxtaposition to other bracketed words and phrases are not unlike magnets that either repel or attract.

Hinrichsen is so inventive with form, this aspect of his work can’t be stressed too strongly. One of his new poems, “[dominion] [I Shall Not Be Saved but I Shall Be Risen] [Our Poverty Her Aloneness My Lip Sync],” starts:

1. [DIRECTIVE]

eat without tasting—that’s how I survived—mother slop shoveled nightly

with a heavy fork and a quick tongue—SWISH of skim—a quicker throat

2. [CONSUMERISM] or [ALL FOR ONE AND ONE FOR ALL WITH ALEXANDRE DUMAS]

a quarter—fifth grade—could last a week those red hot Mondays—tart Tuesdays—

jawbreakers middle of the week—then Wrigley’s Wrigley’s Three Musketeer’s—

this sugar—none at home—the fuel

3. [PORTRAIT OF MY MOTHER WITH OLIVES IN IT]

woe is woe-/word cannot touch it—therefore martini—Sinatra—night

And there’s that song reference again! Captain Beefheart even gets a nod in “[schema geometrica] [w/Instragram Model Kaylen Ward & a Yangtze River Paddlefish].”

In an appendix to Dominion, the reader can scan a QR code to listen to poems from Hinrichsen’s 1983 book, The Attraction of Heavenly Bodies and from his 2002 book, The Rain that Falls this Far.

Dennis Hinrichsen also writes about the effects of global greed, the excesses of capitalism and industrialism, the exploitation of labor, the nuclear age, as well as personal issues. But throughout, there’s an aching tension between the inevitable and the sublime in Dennis Hinrichsen’s poetry, and it’s impossible to know what that balance really is, where we cross a line, what we cross into.

Charles Rammelkamp

To order this book click here

Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore, where he lives, and edits The Potomac, an online literary journal. http://thepotomacjournal.com. His photographs, poetry and fiction have appeared in many literary journals. His latest book is a collection of poems called Mata Hari: Eye of the Day (Apprentice House, Loyola University), and another poetry collection, American Zeitgeist, is forthcoming from Apprentice House.

Harry Man, Popular Song,

Nine Arches Press, 2024,

ISBN 9781913437909, £11.99, 74pp.

The clue to decoding Man’s eagerly awaited collection is in the title: if you are not familiar with popular culture, be it David Bowie, the films of Arnold Schwarzenegger, and computer games such as The Legend of Zagor, you will drift a little, comfortably supported by a lifejacket composed of poetic craft, wit, and serious insights into the business of being human which make them accessible to the non-cognoscenti.

The list of acknowledgments is testimony to the extant success of Man’s poetry; whether longlisted in the National Poetry Collection or displayed on a station platform, these cunning, curious poems engage and tease the reader. In addition to the interests mentioned above, Man focuses on the extra-terrestrial, but also provides tender and sharp perspectives on such mundane issues as reading Tennyson during a break in a night shift; camping on a cold night; and tree-spotting, from which we learn that ‘… our roots/show above and below the surface’, a neat way of commenting on how our identities are formed by where we’ve come from as well as where we aspire to be.

At times, Man uses a direct approach to his subject; he wants to do his best to: ‘ … pin in your mind/the particularity of each star’s tiny-bigness’. (Almost There).

The esoteric references are put to good use: ‘Who Dares Challenge Me? The President and CEO of the Company that Emits more C02 than Any Other in the World’s Statement on Third Quarterly Earnings Translated Using the Language of 90s Cult Boardgame The Legend of Zagor’ does what it says on the tin: Man’s ironic use of this particular lexicon cuts through the bs.

Sometimes the joke seems to be taken to extremes; the two page poem riffing on Coleridge (If Xanadu Did Future Calm) requires no fewer than three pages of notes to explain the references to contemporary or projected technologies. ‘Alphabets of the Human Heart in Languages of the World’ likewise uses more words in its footnotes (in this case helpfully at the bottom of the page rather than at the back of the book) than in the poem itself; perhaps not one for listening to rather than reading, though I can testify to Man being a captivating performer.

Nine Arches Press is an innovative and adventurous press, offering mentoring opportunities through its ‘Primer’ competition, as well as both a journal and regular blog. Man’s exciting and original work is well placed with such a prestigious publisher. Buy this book; read it first with your thumb in the back for the notes. Reread to simply luxuriate in the language.

Hannah Stone

Hannah Stone is the author of Lodestone (Stairwell Books, 2016), Missing Miles (Indigo Dreams Publishing, 2017), Swn y Morloi (Maytree Press, 2019) and several collaborations, including Fit to Bust with Pamela Scobie (Runcible Spoon, 2020). She convenes the poets/composers forum for Leeds Leider, curates Nowt but Verse for Leeds Library, is poet theologian in Virtual Residence for Leeds Church Institute and editor of the literary journal Dream Catcher. Contact her on hannahstone14@hotmail.com for readings, workshops or book purchases.